The terminology

(Adapted from SUSANA-WG12 2009)

Gender identifies the social relationships between women and men. In these, power differences play a major role. Gender is socially constructed; gender relations are contextually specific and often change in response to altering circumstances (MOSER 1993). Class, age, race, ethnicity, culture, religion and urban/rural contexts are also important underlying factors of gender relations.

Gender equality is the equal visibility, opportunities and participation of women and men in all spheres of public and private life; often guided by a vision of human rights, which incorporates acceptance of equal and inalienable rights of women and men. Gender equality is not only crucial for the wellbeing and development of individuals, but also for the evolution of societies and the development of countries. However, gender equality is not yet a fact and although important progress is made (e.g. regarding universal school enrolment, women’s access to the labour market, and women gaining political ground), gender inequality is one of the most pervasive forms of inequality worldwide (UNDP 2005; UNFPA 2005; UN 2007).

The access to clean water and basic sanitation has been declared a basic human right and it is essential for achieving gender equality, sustainable development and poverty alleviation.

Gender, water and sanitation

(Adapted from SUSANA-WG12 2009; WECF 2007; GWA 2006 and UN WATER 2006)

In most societies, women have the primary responsibility for the management of household water supply, sanitation and health. Water is necessary not only for drinking, but also for food production and preparation, care of domestic animals, personal hygiene, care of the sick, cleaning, washing and waste disposal. Because of their dependence on water resources, women have accumulated considerable knowledge about water resources, including location, quality and storage methods. However, efforts geared towards improving the management of the world’s finite water resources and extending access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation, often overlook the central role of women in water management (compare to the principles of IWRM).

One of the most observable divides between women and men, especially in developing countries, is in sanitation and hygiene. The provision of hygiene and sanitation are often considered women’s tasks. Women are promoters, educators and leaders of home and community-based sanitation practices. However, women’s concerns are rarely addressed as societal barriers often restrict women’s involvement in decisions regarding toilets, sanitation program and projects. And in many societies, women’s views ― as opposed to those of men ― are systematically under-represented in decision-making bodies (see also hygiene frameworks and approaches).

Women and children often bear the brunt of the lack of toilets and other sanitation facilities. Women, more than men, suffer the indignity of being forced to defecate and urinate in the open, where they often have to walk to remote locations outside the village leaving women vulnerable to assault and potential rape (COHRE et al. 2008). The majority of those using public defecation areas, where hygienic conditions are often poor and disease is close, are women. In the absence of sanitary facilities, women often have to wait until dark to go for toilet. That is why women often drink less, causing all kinds of health problems. Attempting to ‘hold out’ until the evening may result in physical harm, such as urinary tract infections. People may also attempt to modify their diets, by not eating certain fibrous foods such as pulses or leafy vegetables. An unbalanced diet may result in negative long-term health consequences.

In rural areas of many regions, men often do not use stinky pit latrines and relieve themselves in the open, whereas women are dependent on the pit latrines several times a day. In urban areas women and girls face innumerable security risks and other dangers when they use toilets shared with men. Research in East Africa indicates that safety and privacy are women’s main concerns for sanitation (HANNAN and ANDERSSON 2002). With the lack of safe sanitation women’s dignity, safety and health are at stake.

Responsibilities, construction and maintenance

(Adapted from SUSANA-WG12 2009; COHRE et al. 2008; INTERMEDIATE TECHNOLOGY GROUP 2005 and UN WATER 2006)

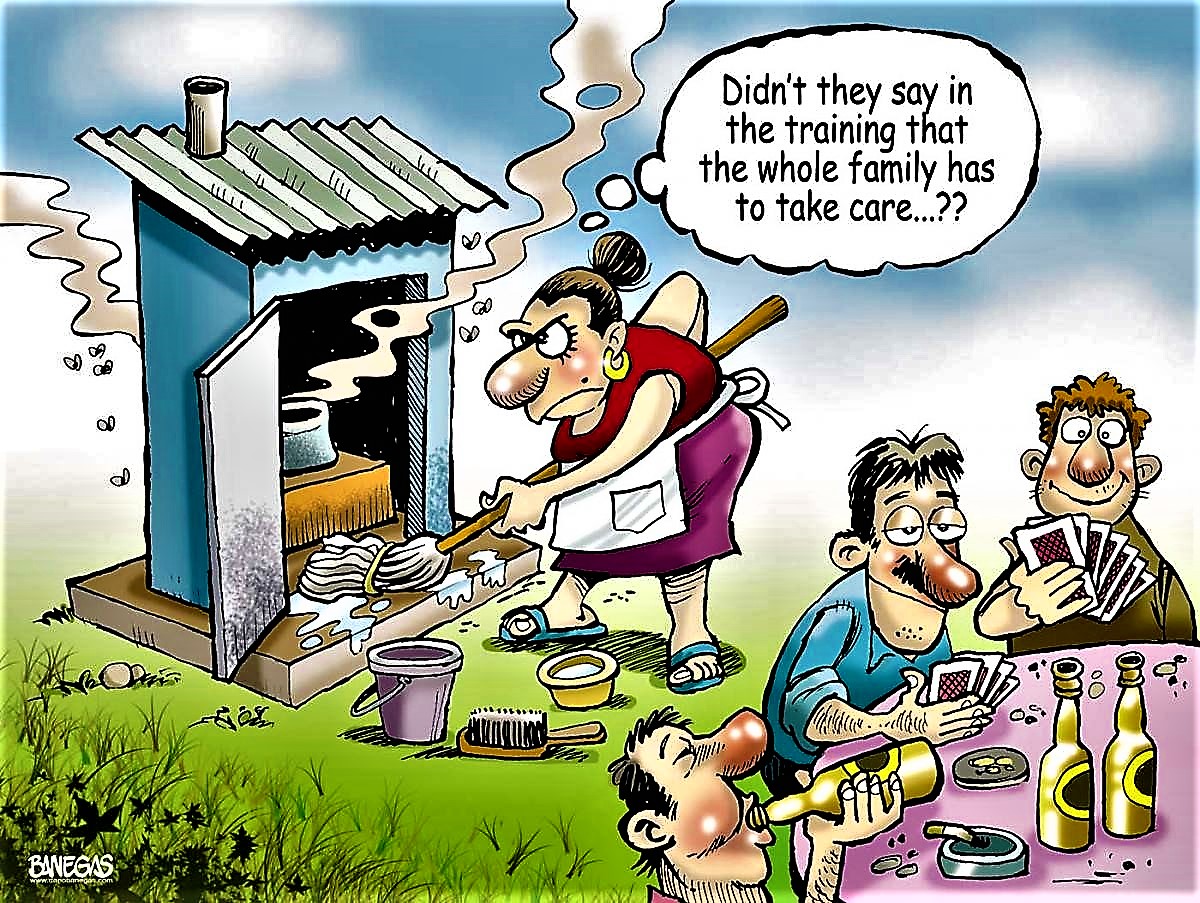

Whereas the cleaning of toilets is primarily the responsibility of women, construction and maintenance of pit latrines (digging, repairing and exhausting) is primarily done by men (HANNAN and ANDERSSON 2002). However, in some regions, the task of emptying the latrines falls exclusively on the shoulders of poor women, and the labour-conditions under which they do this work are appalling. In many households, women are also responsible for making sure there is sufficient water for sanitation and there are many cases where women have to pay for water from limited household budgets. Despite the role of women in hygiene and sanitation at household level, toilet construction program that provide income-generation opportunities often presume that only men will be interested in or suited for those tasks.

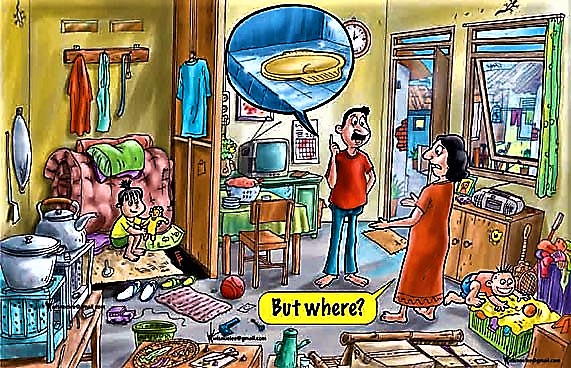

In the design, location and construction of toilets and sanitation blocks, inadequate attention is paid to the specific needs of women and men, boys and girls. Sanitation program, as with many other development program, have often been built around assumptions of some gender-neutrality. This results in gender-specific failures, such as, toilets with doors facing the street in which women feel insecure, school urinals that are too high for boys, absence of disposal for sanitary materials by women, pour-flush toilets that require considerably more work for women in transporting water. Also, sanitation blocks are sometimes used for multiple functions, including washing and drying, shelter from rain etc., but are not designed for these purposes.

A combination of discrimination, lack of political will or attention, and inadequate legal structures result in neglect of women’s needs and lack of their involvement in sanitation development and planning. The majority of the world’s one billion people living in poverty are women, and the feminisation of poverty, particularly among women-headed households, continues to grow. Land tenure is a significant stumbling block as well; worldwide women own only up to 2% of all land, and therefore often lack access to related assets and resources, including water and land for toilet construction.

During the World Water Forum 4, in Mexico City in 2006, local actions on gender in water and sanitation in Armenia, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Mexico were shared. It was demonstrated that a stronger involvement of civil society groups, in particular women and minority groups, in decision making on sanitation and wastewater management is often necessary to achieve a breakthrough in the sector (WECF n.y.).

Gender and school sanitation

(Adapted from SUSANA-WG12 2009; COHRE et al. 2008)

School sanitation is a neglected problem in many parts of the world. Hygienic conditions are often very poor, meaning that hand-washing facilities as well as separate individual cabins and anal cleansing materials for the pupils are missing in many toilets and that the deplorable conditions often do not comply with human dignity for boys and girls. Children and teachers often do not drink adequately in order to avoid the toilet visit, which has negative impact on their health (see also school campaigns).

Girls, particularly at and after puberty, do miss school or even drop out of their schools due to the lack of sanitary facilities, and/or the absence of separation of girls’ and boys’ toilets. In these situations, girls also stay away from school when they are menstruating (GWA 2006; HANNAN and ANDERSSON 2002). In rural Pakistan for instance, more than 50% of girls drop out of school in grade 2-3 because the schools do not have latrines (UNICEF 2008). An assessment in 20 schools in rural Tajikistan revealed that all girls choose not to attend when they have their periods, as there are no facilities available (MOOIJMAN 2002). Lack of adequate toilets and hygiene in schools is a key critical barrier to girl school attendance and girls education. If sanitation facilities fail, women might not attend (vocational) training and meetings (GWA 2006). Simple measures, such as providing schools with water and safe toilets, and promoting hygiene education in the classroom, can enable girls school attendance, and reduce health-related risks for all (UN WATER 2006).

Gender issues in sustainable sanitation

(Adapted from SUSANA-WG12 2009; HANNAN and ANDERSSON 2002)

Apart from the gender-specific issues mentioned, the gender perspectives of sustainable sanitation projects have not been fully explored yet. HANNAN and ANDERSSON (2002) remind us that women are actively involved in food crop production and food security in many parts of the world, and would be directly affected by increased soil nutrients provided through ecological sanitation solutions, for their rural and urban agriculture (see e.g. use of urine and faeces in agriculture).

For example, composting toilets in use in South India require much less water than water flush toilets, favoured by more well off families. This reduces the work burden for women in providing water for the toilets. In Zimbabwe women in some rural areas preferred the waterless alternative - the arborloo ― to the conventional pit latrines as they can be built closer to the house. Filled pits are used by women for planting fruit trees while men expressed appreciation of the Arborloo because the pits are smaller and require less labour in building.

Women’s attitudes towards urine diverting dry toilets (UDDT) seem to be more positive than those of men. Women would like to have the toilets in house, as that would reduce walking distances also during bad weather conditions, but often there is not enough room in the house. They are also often more willing to use the fertiliser in their fields and gardens. Therefore women and children (via schools - see invalid link) could play an important role in motivating and educating others to use reuse-oriented toilets (see also recharge and reuse).

Some experts, however, warn for the fact that sustainable sanitation systems such as UDDTs require more work in cleaning, maintenance, and application of urine and faeces. Women do much of that work, so that could add to their work burden. Therefore, it is important to closely monitor these projects and operations in a gender specific way. Also, women need more education because it is not allowed to throw tampons and other menstruation materials in the toilets (especially in the UDDTs) and the use of urine diverting toilets is a little more complicated for women.

Gender mainstreaming in sanitation

(Adapted from SUSANA-WG12 2009; ADB 1998; ADB 2006 and GWA 2006)

In order to achieve gender equality, women’s empowerment and full participation are important strategies. The process to thoroughly integrate a gender perspective in institutions and operations is called gender mainstreaming. According to the ECOSOC definition gender mainstreaming is: “the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or program, in any area and at all levels. It is a strategy for making the concerns and experiences of women as well as of men an integral part of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and program in all political, economic and societal spheres, so that women and men benefit equally, and inequality is not perpetuated. The ultimate goal of mainstreaming is to achieve gender equality" (ECOSOC 1997).

As has been argued above, there is an urgent need to bring a gender perspective into the sanitation and hygiene sector, and to involve and address both women and men in these efforts. Gender mainstreaming leads to benefits that go beyond good water and sanitation performance, including economic benefits, empowerment of women, more gender equality and benefits to children.

Gender mainstreaming works best through an adaptive, process-oriented approach, that is participatory and responsive to the needs of the poor. Specific institutional arrangements are necessary to ensure that gender is considered an integral part of efficient and effective planning and implementation. This encompasses, for example, the development of gender policies and procedures, commitment at all organisational levels, the availability of ― internal or external ― gender expertise. Gender must be addressed in policy formulation and by-laws (see policies and legal framework). The following elements of the gender mainstreaming process can safeguard a gender perspective in sustainable sanitation.

A gender analysis helps in understanding the socioeconomic and cultural concerns in a project area. At the end of this chapter a list of guiding questions provides the framework for such an analysis. A gender analysis builds understanding of demands and needs of women and men, their respective knowledge and expertise, attitudes and practices, and it draws light on the constraints for women’s and men’s participation in activities (see also stakeholder analysis). In order to make such an analysis, gender disaggregate data and involvement of women and men in sanitation planning, construction and maintenance are needed (UN Water 2006).

It is also important to assess the impact of policies and program on women and men, of different social and age groups. The question should be raised who benefits and who bears the burdens/face drawbacks of these policies and program.

Project teams in the field should strive for a gender balance and be sensitive to gender and related cultural concerns. Selecting field team members with gender awareness, local knowledge, cultural understanding and willingness to listen can improve this.

To ensure women’s participation and involvement, leadership and management training for women can be important project components. Also the training of women to help run and maintain sanitation facilities are part of such empowerment processes.

Financing and budget allocations are often major constraints, as most of the governments delegate the support for and financing of sanitation facilities to local governments. However, the right investments in sanitation and hygiene usually pay off. Adequate resources should be allocated to implement gender strategies in the sector. Gender responsive budgeting could be a useful tool to make sure that women and girls also benefit from hygiene and sanitation efforts.

As not all women (and men) are the same, it is important to classify them amongst different groups: women and men from different age groups, classes, castes and ethnicity, women and men living in poverty, as refugees, and in female-headed households.

In gender mainstreaming in sanitation, one has to be aware of a few pitfalls: (adapted from ADB Asia Water Watch 2015)

- Women may be encouraged to take on sanitation management roles and additional work, but they might receive no additional resources or influence to perform these tasks. This could be the case in particular for UDDT systems, where more maintenance work is required than for pit latrines.

- The introduction of a ‘user pays’ system for toilets and other sanitation facilities may cause a considerable burden for women, particularly for those living in poverty. On the other hand there are also studies showing that women are willing to pay for hygienic and safe toilets.

- If hygiene education is identified solely as a ‘women’s area’, men may stay away from those, and those components may be seen as less important.

- Women may receive more training, but may be prevented from putting their own skills and knowledge into practice by cultural or social norms.

In order to succeed in bringing a gender perspective in sustainable sanitation policies and program, it is imperative to also involve men, enable them to share their views on gender issues and promote their gender sensitivity. Women as well as men have to be recognised as important actors, stakeholders and change-agents in households and communities.

Some guiding questions

(Adapted from SUSANA-WG12 2009; COHRE et al. 2008; UN WATER 2006; ADB 1998; ADB 2006; UNICEF 2008 and VAN WIJK-SYBESMA 1998)

Without a gender perspective in sustainable sanitation and hygiene policies and efforts, unexpected side effects can occur, such as adding extra burdens for women or men and/or that the constructed facilities do not meet the needs of women and girls. On the other hand mainstreaming a gender perspective in the sector can add to its effectiveness and efficiency. The following guiding questions can be helpful in the process of integrating a gender perspective in sustainable sanitation planning, design and implementation.

Gender analysis:

- Have you investigated the gender issues related to sanitation provision and use in the project area?

- Are women’s (and men’s) needs, interests and priorities regarding sanitation clear?

- What are the gender-specific elements in the sanitation policies and strategies of the government, company or institution?

- Did you use a gender perspective to gather information? Are the gathered data sex-disaggregate?

Institutional aspects:

- Is expertise in social development, sanitation and hygiene education available in the organisation, project or program team?

- Are women and men fully involved in the organisation and have internal discriminatory factors been tackled successfully?

- Are there any constraints for women and/or men to access and control over resources?

Gender impact assessment:

- Will the program objectives and activities have an impact on existing inequalities between women and men, boys and girls?

- How will the program affect women and men? E.g. will their work burdens be in/decreased; their health be affected; economic benefits reached. Is there gender balance in the burdens and benefits?

- Is the budget gender sensitive?

- Gender Specific Monitoring and Evaluation: Do you measure and monitor for separate effects on women, men, girls and boys? How?

Location and design:

- Does the design and location of sanitation facilities reflect the needs of women and men?

- Are toilets situated in such a way that physical security of women and girls is guaranteed?

- Is the location close to home and is the path well accessible and well lit?

- Are separate toilets for women and men, boys and girls constructed and maintained (e.g. in schools, factories, public places)?

Technology and resources:

- Does the technology used reflect women’s and men’s priorities and needs?

- Is the technical and financial planning for ongoing operation and maintenance of facilities in place? And how are women involved?

- Have funds been earmarked for separate sanitation facilities for girls and boys, and for hygiene education in school curricula? (See also school campaigns)

Empowerment and decision-making:

- Is women’s capacity developed and their participation in training encouraged?

- Are women and girls enabled to acquire access to relevant information, training and resources?

- Is there gender balance in decision-making?

- Are women involved in the planning (incl. location and quality) and management of sanitation services?

- Have hygiene education messages been promoted through women’s groups, schools and health clinics?

Gender Guidelines in Water Supply and Sanitation. Checklist

Setting the Scene: Water, Poverty, and the MDGs. Asia Water Watch 2015

Sanitation: A human Rights Imperative

A document defining sanitation in human rights terms, describing the value of treating sanitation as a human rights issue and outlining priority actions for governments, international organisations and civil society.

COHRE ; WATERAID SDC ; UN-HABITAT (2008): Sanitation: A human Rights Imperative. Geneva: Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE)Mainstreaming the gender perspective into all policies and agendas in the United Nations system

Sanitation and Hygiene. Chapter 3.4

Gender Perspectives on Ecological Sanitation

Environmental Sanitation, Livelihoods & Gender, from: Sanitation, Hygiene and Water Services among the Urban poor

Assessment of 1994-2001 UNICEF School Sanitation and Hygiene Project in Khation Tajikistan

Gender Planning and Development: Theory, Practice and Training

SuSanA Factsheet: Integrating a Gender Perspective in Sustainable Sanitation

This publication gives good background information on the pressing need to integrate a gender perspective into the efforts to promote safe and sustainable sanitation. Most of the information from the text above is taken from this factsheet.

SUSANA (2009): SuSanA Factsheet: Integrating a Gender Perspective in Sustainable Sanitation. Eschborn: Sustainable Sanitation Alliance Working Group on Gender URL [Accessed: 10.10.2012]The Millennium Development Goals Report

Human Development Report 2005

State of the World Population 2005

Water, Environment and Sanitation. 10 Key Points to Check for Gender Equity; a checklist for managers of water and sanitation programs

Gender, Water and Sanitation: a Policy Brief

A policy brief on the UN approach to addressing Gender in the areas of water and sanitation.

UN WATER (2006): Gender, Water and Sanitation: a Policy Brief. New York: United Nations URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Gender in Water Resources Management, Water Supply and Sanitation: roles and realities revisited

Fact Sheet on Ecological Sanitation and Hygienic Considerations by Women

Water and Sanitation from a Gender Perspective at the World Water Forum 4, Mexico, 13-21 March 2006

Sanitation and Hygiene. Chapter 3.4

WSP Cartoon Calendar

Gender Check List, Water Supply and Sanitation

This publication focuses on key questions and action points in project cycle, gender analysis, project design, policy dialogue.

ADB (2002): Gender Check List, Water Supply and Sanitation. Manila: Asian Development Bank (ADB) URL [Accessed: 17.04.2012]Gender Guidelines: Water Supply and Sanitation. Supplement to the guide to gender and development

This guideline document focuses particularly on gender implications in water and sanitation, including guiding principles and general recommendation during implementation and monitoring of water and sanitation programs/projects.

AUSAID (2005): Gender Guidelines: Water Supply and Sanitation. Supplement to the guide to gender and development. Sydney: AUSAID URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Addressing Social and Gender Equity in the Water Sector

Most discussions around 'water scarcity' fail to highlight that this scarcity is skewed towards those who are vulnerable in terms of caste, gender, class, location. This paper analyses the social composition of 'scarcity' and the conflicts that arise from it. It emphasises that the various domains that the water sector is composed of (such as the household, the village etc) are non-homogenous and have potential for both conflict and cooperation. This reality shapes the phenomenon of water scarcity and needs to be understood.

BHAT, S. POMANE, R. KULKARNI, S. (2012): Addressing Social and Gender Equity in the Water Sector. (= Water Policy Research Highlight , 22 ). Gujarat, India: IWMI-Tata Water Policy Program URL [Accessed: 15.01.2013]Gender Sanitation and Hygiene

A document emphasising the focus on gender differences as one of particular importance with regard to hygiene and sanitation initiatives and as well as encouraging gender-balanced approaches in all sanitation hygiene plans and approaches.

GWA (2005): Gender Sanitation and Hygiene. Dieren: Gender and Water Alliance (GWA) URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Global Review of Sanitation System Trends and Interactions with Menstrual Management Practices

The problem with disposing of menstrual waste into pit latrines is that it causes the pits to fill up faster. The excreta in the pit decompose and decrease in volume, while the non-biodegradable components of menstrual waste accumulate and do not break down. Furthermore, once the sludge has been removed from the pit latrine, if it is to be used in agriculture, any waste that has not completely decomposed such as menstrual pads must be removed before the sludge can be composted or applied to farmland. The cost to remove, screen, and dispose of menstrual management products from pit latrine sludge is high and not accounted for.

KJELLEN, M. PENSULO, C. NORDQVIST, P. FODGE, M. (2012): Global Review of Sanitation System Trends and Interactions with Menstrual Management Practices. Report for the Menstrual Management and Sanitation Systems Project . Stockholm: Stockholm Environment Institute URL [Accessed: 15.01.2013]Mainstreaming Gender in Water Resources Management, Background Paper for the World Vision Process

The publication focuses on a gender approach in sustainable water management and examples from the field.

MAHARAJ, N. (1999): Mainstreaming Gender in Water Resources Management, Background Paper for the World Vision Process. Paris: World Water Vision Unit, World Water Council URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]SuSanA Factsheet: Integrating a Gender Perspective in Sustainable Sanitation

This publication gives good background information on the pressing need to integrate a gender perspective into the efforts to promote safe and sustainable sanitation. Most of the information from the text above is taken from this factsheet.

SUSANA (2009): SuSanA Factsheet: Integrating a Gender Perspective in Sustainable Sanitation. Eschborn: Sustainable Sanitation Alliance Working Group on Gender URL [Accessed: 10.10.2012]Gender and Sanitation, breaking taboos, improving lives

This document highlights the importance of good sanitation and hygiene practices and the involvement of women in decision-making to ensure that new sanitation initiatives are appropriate for all.

TEARFUND (2008): Gender and Sanitation, breaking taboos, improving lives. Teddington: TEARFUND URL [Accessed: 17.04.2012]Framework for Gender Mainstreaming Water and Sanitation for Cities

This material presents a framework for gender mainstreaming in water and sanitation and highlights critical issues related to gender, water and sanitation services in urban areas.

UN HABITAT (2006): Framework for Gender Mainstreaming Water and Sanitation for Cities. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Gender, Water and Sanitation: a Policy Brief

A policy brief on the UN approach to addressing Gender in the areas of water and sanitation.

UN WATER (2006): Gender, Water and Sanitation: a Policy Brief. New York: United Nations URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Kashkadarya and Navoi Rural Water Supply and Sanitation project. Gender Action Plan

Gender Mainstreaming Impact Study

This impact assessment identifies how the water and sanitation initiatives implemented under the Water Sanitation and Infrastructure Branch of UN-HABITAT, have strategically mainstreamed gender aspects in its various initiatives. It shows achievements and impact, challenges, lessons learned and provides recommendations.

UN HABITAT (2011): Gender Mainstreaming Impact Study. (= Water and Sanitation Trust Fund Impact Study Series , 4 ). Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) URL [Accessed: 17.10.2011]Sanitation Brings Dignity, Equality and Safety

This short factsheet informs about how sanitation is connected with questions of dignity, equality and safety, including questions of gender, disabilities, etc.

UN WATER (n.y): Sanitation Brings Dignity, Equality and Safety. (= Factsheet , 3 ). United Nations Water (UN WATER) URL [Accessed: 17.10.2011]Gender in Water and Sanitation

Gender in Water and Sanitation highlights in brief form, approaches to redressing gender inequality in the water and sanitation sector. It is a working paper as the Water and Sanitation Program and its partners continue to explore and document emerging practice from the field. The review is intended for easy reference by sector ministries, donors, citizens, development banks, non-governmental organizations and water and sanitation service providers committed to mainstreaming gender in the sector.

WSP (2012): Gender in Water and Sanitation. Washington, D.C: Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) URL [Accessed: 27.02.2012]School Menstrual Hygiene Management in Malawi: More than Toilets

This study identifies the needs and experiences of girls regarding menstruation. It draws upon participatory group workshops, a questionnaire and semi structured interviews with school-age girls in Malawi to make various recommendations, including lessons about menstrual hygiene management (MHM), girl-friendly toilet designs, and the provision of suitable and cheap sanitary protection.

PIPER-PILLITTERI, S. (2012): School Menstrual Hygiene Management in Malawi: More than Toilets. London: WaterAid URL [Accessed: 17.03.2012]Ecodesign: The Bottom Line

There is no single design solution to sanitation. But there are universal principles for systematically and safely detoxifying human excreta, without contaminating, wasting or even using water. Ecological sanitation design — which is focused on sustainability through reuse and recycling — offers workable solutions that are gaining footholds around the world, as Nature explores on the following pages through the work of Peter Morgan in Zimbabwe, Ralf Otterpohl and his team in Germany, Shunmuga Paramasivan in India, and Ed Harrington and his colleagues in California.

NATURE (Editor) ; MORGAN, P. ; OTTERPOHL, R. ; PARAMASIVAN, S. ; HARRINGTON, E. (2012): Ecodesign: The Bottom Line. In: Nature: International Weekly Journal of Science: Volume 486 , 186-189. URL [Accessed: 19.06.2012]Sanitation Matters - A Magazine for Southern Africa

Content in this issue: A Tool For Measuring The Effectiveness Of Handwashing p. 3-7; Five Best Practices Of Hygiene Promotion Interventions In the WASH Sector p. 8-9; Washing Your Hands With Soap: Why Is It Important? p. 10-11; Appropriate Sanitation Infrastructure At Schools Improves Access To Education p. 12-13; Management Of Menstruation For Girls Of School Going Age: Lessons Learnt From Pilot Work In Kwekwe p. 14 -15; WIN-SA Breaks The Silence On Menstrual Hygiene Management p. 16; Joining Hands To Help Keep Girls In Schools p. 17; The Girl-Child And Menstrual Management :The Stories Of Young Zimbabwean Girls. p. 18-19; Toilet Rehabilitation At Nciphizeni JSS And Mtyu JSS Schools p. 20 - 23; Celebratiing 100% sanitation p. 24 - 26.

WATER INFORMATION NETWORK (2012): Sanitation Matters - A Magazine for Southern Africa. South Africa: Water Information Network URL [Accessed: 19.06.2019]Equity of Access to WASH in Schools: A Comparative Study of Policy and Service Delivery

This study presents findings from a six-country study conducted by UNICEF and the Center for Global Safe Water at Emory University in collaboration with UNICEF country offices in Kyrgyzstan, Malawi, the Philippines, Timor-Leste, Uganda and Uzbekistan and their partners. The six case studies presented together contribute to the broader understanding of inequities in WASH in Schools access by describing various dimensions that contribute to equitable or inequitable access across regions, cultures, gender and communities.

UNICEF (2013): Equity of Access to WASH in Schools: A Comparative Study of Policy and Service Delivery. New York: UNICEF URL [Accessed: 17.04.2013]Language: Spanish

We Can't Wait

This report is on the impact of poor sanitation on the safety, well-being, and educational prospects of women. Girls’ lack of access to a clean, safe toilet, especially during menstruation, perpetuates risk, shame, and fear. This has long-term impacts on women’s health, education, livelihoods, and safety but it also impacts the economy, as failing to provide for the sanitation needs of women ultimately risks excluding half of the potential workforce.

WATERAID ; UNILEVER DOMESTOS ; WSSCC (2013): We Can't Wait. A Report on Sanitation and Hygiene for Women and Girls. London / Geneva: WaterAid, Unilever Domestos, Water Supply & Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) URL [Accessed: 11.01.2014]Assessing the Role of Women in Microfinance for Water Supply and Sanitation Services

This article assesses the role of women in microcredit programmes and the possibility to empower women through such programmes to give them a bigger voice.

WALDORF, A. (2013): Assessing the Role of Women in Microfinance for Water Supply and Sanitation Services. In: The Journal of Gender & Water wH2O: Volume 2 , 28-30. URL [Accessed: 04.02.2014]Making Sanitation and Hygiene Safer - Reducing Vulnerabilities to Violence

This issue of Frontiers of CLTS focuses on the issue of safety and vulnerabilities to violence that women, girls and sometimes boys and men can face which are related to sanitation and hygiene. It points out areas in which CLTS methodologies, if not used skilfully with awareness and care, can run the potential risk of creating additional vulnerabilities, for example as a by-product of community pressure to reach ODF. It also looks at good practices within organisations to ensure that those working in the sector know how to programme to reduce vulnerabilities to violence and to ensure that sector actors also do not become the perpetrators of, or face violence.

HOUSE, S. ; CAVILL, S. (2015): Making Sanitation and Hygiene Safer - Reducing Vulnerabilities to Violence. In: Frontiers of CLTS: Innovations and Insights: Volume 5 URL [Accessed: 15.06.2015]Eliminating Discrimination and Inequalities in Access to Water and Sanitation

This policy brief aims to provide guidance on non-discrimination and equality in the context of access to drinking water and sanitation, with a particular focus on women and girls. It also informs readers on the duty of States and responsibilities of non-State actors in this regard.

VAN DE LANDE, L. (2015): Eliminating Discrimination and Inequalities in Access to Water and Sanitation. Geneva, Switzerland: UN-Water URL [Accessed: 11.05.2016]Integrating Gender into the Promotion of Hygiene in Schools SSHE

This case study addresses gender imbalances among students and ensuring the participation of the entire community to actively participate for the success of the project.

ALOUKA (n.y): Integrating Gender into the Promotion of Hygiene in Schools SSHE. Effumani: URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Egypt: Empowering Women’s Participation in Community and Household Decision-making in Water and Sanitation

This case study an women’s participation in community and household decision-making in water and sanitation responding to the needs of marginalized communities while promoting changes in traditional gender roles in Egypt.

HAMMAM, G. M. (2004): Egypt: Empowering Women’s Participation in Community and Household Decision-making in Water and Sanitation. Nazlet Fergalla: URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Gender Equality as a Condition for Access to Water and Sanitation

This case study from Nicaragua focuses on the access to water and sanitation as a human right, one that should be attainable by all men, women and children in equal condition and opportunities.

LANUZA (2003): Gender Equality as a Condition for Access to Water and Sanitation. URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Women in Sanitation and Brick-making Project. Mabule Village

This case study gives insights on a sanitation and brick-making project empowering South African women whose husbands were migrant workers and leaving them the full responsibility of managing the available household resources.

MASONDO (n.y): Women in Sanitation and Brick-making Project. Mabule Village. South Africa: URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Gender Integration in a Rural Water Project in the Samari-Nkwanta Community

This is a case study, promoting gender equality: a shift from male dominance to a more equitable sharing of power and decision-making.

POKU SAM (1997): Gender Integration in a Rural Water Project in the Samari-Nkwanta Community. Ghana: URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Gender equity, water and food security in drought prone areas

Drought is stressful for all, but some sections of society are more vulnerable than others. This paper takes a look at how gender inequities are worsened by lack of food security. It also points out that despite women's active participation in land and water based activities, they rarely are involved in decision making or ownership. It suggests policy changes that may enhance womens access and resources.

SAHU, B. (2012): Gender equity, water and food security in drought prone areas. A case study of Odisha and Gujarat. (= Water Policy Research Highlight , 28 ). Gujarat, India: IWMI-Tata Water Policy Program URL [Accessed: 15.01.2013]Gender, Water and Sanitation, Case studies on Best Practices

This publication is a compilation of numerous best practice examples from all over the world with regard to gender, water and sanitation.

UN (2006): Gender, Water and Sanitation, Case studies on Best Practices. New York: United Nations (UN) URL [Accessed: 12.12.2012]From Alienation to an Empowered Community - Applying a Gender Mainstreaming Approach to a Sanitation Project, Tamil Nadu, India

This case study from Tamil Nadu, India is on empowering women and enhancing men’s involvement in development programs through a gender mainstreaming approach.

VICTOR (2000): From Alienation to an Empowered Community - Applying a Gender Mainstreaming Approach to a Sanitation Project, Tamil Nadu, India. URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]The Gender Approach to Water Management

This booklet is one of a series of advocacy materials prepared for the Gender and Water Alliance (GWA) by WEDC, Loughborough University, UK with an international GWA team. See www.genderandwater.org for more info.

GWA (2002): The Gender Approach to Water Management. Findings of an electronic conference series convened by the Gender and Water Alliance. Delft: Gender and Water Aliance (GWA) URL [Accessed: 31.10.2010]Gender and Urban Agriculture: The Case of Accra, Ghana

IWMI research in Ghana suggests that poor access to irrigation may discourage some women from taking up urban farming, but men also feel disadvantaged by female domination of the marketing sector.

HOPE, L. COFIE, O. KERAITA, B. DRECHSEL, P. (2009): Gender and Urban Agriculture: The Case of Accra, Ghana. Warwickshire, UK: Practical Action Publishing URL [Accessed: 26.03.2012]Advocacy Manual for Gender & Water Ambassadors

This Advocacy Manual has been developed to assist members of the Gender and Water Alliance who are involved in advocating for greater attention to gender issues within the water sector. The Manual is principally aimed at GWA members designated as Gender Ambassadors, whose role is to influence debates in international and national water conferences and similar events, as well as in relation to national water policy development, implementation and monitoring.

GWA (2003): Advocacy Manual for Gender & Water Ambassadors. Delft: Gender and Water Alliance URL [Accessed: 31.10.2010]Menstrual hygiene matters

Menstrual hygiene matters is an essential resource for improving menstrual hygiene for women and girls in lower and middle-income countries. Nine modules and toolkits cover key aspects of menstrual hygiene in different settings, including communities, schools and emergencies.

HOUSE, S. MAHON, T. CAVILL, S. (2012): Menstrual hygiene matters. A resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world. London: WaterAid URL [Accessed: 29.01.2013]Calendar 2012: Focusing Attention on the Critical Role of Gender in Water and Sanitation

This year (2012), the World Bank/Water and Sanitation Program’s calendar depicts water and sanitation challenges from a gender perspective to call attention to some of the social norms that result from, and reinforce poor service quality.

WSP (2012): Calendar 2012: Focusing Attention on the Critical Role of Gender in Water and Sanitation. Washington, D.C: Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) URL [Accessed: 27.02.2012]Addressing Water and Sanitation Needs of Displaced Women in Emergencies

Mainstreaming gender in an emergency Water and Sanitation response can be difficult as standard consultation and participation processes take too much time in an emergency. To facilitate a quick response that includes women's needs, a simple Gender and WatSan Tool has been developed that can also be used by less experienced staff.

LANGE, R. de (2013): Addressing Water and Sanitation Needs of Displaced Women in Emergencies. (= WEDC International Conference, Nakuru, Kenya , 36 ). Leicestershire: Water, Engineering and Development Centre (WEDC) URL [Accessed: 11.01.2014]Closing the Gender Gap: Punjab Water Supply and Sanitation Project

This paper summarises the planning, design and implementation of gender specific components that made the water supply project successful. It shows how one water supply project developed female beneficiaries to become leaders and how men recognized their potentials.

ADB (2008): Closing the Gender Gap: Punjab Water Supply and Sanitation Project. Manila: Asian Development Bank (ADB) URL [Accessed: 17.04.2012]Water, Sanitation and Gender: Gender and Development Briefing Notes

This publication is addressing gender in water and sanitation and how it improves hygiene and sustainability, which includes the potential to make economic change.

WORLDBANK (2007): Water, Sanitation and Gender: Gender and Development Briefing Notes. Washington D.C.: Gender and Development Group, The World Bank URL [Accessed: 26.08.2010]Making Connections. Women Sanitation and Health Event 29 April 2013

On 29th April, SHARE Research Consortium hosted the event 'Making connections: Women, sanitation and health'. It brought together a diverse mix of speakers from the WASH, gender and health sectors to debate issues such as violence against women, menstrual hygiene management and maternal health.

SHARE (2013): Making Connections. Women Sanitation and Health Event 29 April 2013. (= Proceedings of the Women Sanitation and Health Event, 19th of April 2013). London: Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) URL [Accessed: 15.05.2013]Gender Checklist: Water Supply and Sanitation

This link is a checklist on water supply and sanitation. It focuses on why gender is important on water supply and sanitation projects.

http://www.genderandwater.org/

This link highlights the effects of gender differences with regard to hygiene and sanitation initiatives, and further encourages gender balance approaches in hygiene and sanitation plans.

http://www.genderandwater.org/

The mission of GWA is to promote women’s and men’s equitable access to and management of safe and adequate water, for domestic supply, sanitation, food security and environmental sustainability. GWA believes that equitable access to and control over water is a basic right for all, as well as a critical factor in promoting poverty eradication and sustainability. It contains materials in French, Spanish, Portuguese and Arabic.

www.guardian.co.uk

This article shows the link between improved sanitation, sexual (gender) discrimination and health issues.

Gender mainstreaming in water and sanitation

This link highlights the importance of gender mainstreaming to achieve gender balance and reduce inequality.

www.unwaterlibrary.org/gender

This virtual library provides access to recent water and sanitation related publications produced by the United Nations system. This chapter shows the results on the theme "Gender and Water".

http://www.wecf.eu

Women in Europe for a Common Future (WECF) is an NGO dedicated to safeguarding our future by creating a healthy environment and sustainable development for all. It strives for balancing environment, health and economy, and enables women and men to participate at local and global level in policy processes for sustainable development. The website also contains a selection of publications on sutainable sanitation approaches.

http://maternalhealthtaskforce.org/wash-and-womens-health/

Blog on issues relating to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) with a focus on women’s health.

http://www.shareresearch.org/making_connections

Videos of the Presentations at the Women, Sanitation and Health Event on 29th April 2013. It brought together a diverse mix of speakers from the WASH, gender and health sectors to debate issues such as violence against women, menstrual hygiene management and maternal health.

http://www.washdoc.info/

IRC Sanitation Pack, SanPack for short, contains an overview of available methods, techniques and tools in a low-cost, non-sewered sanitation service model, including gender-related issues. It is a reference guide containing links to relevant documents explaining the different stages in the sanitation cycle.

http://www.inclusivewash.org.au/

This website is focussed on Equity and Inclusion in the entire WASH sector and beyond. It aims to provide practical skills and evidence to support practitioners’ implementation of WASH projects in and equitable and inclusive way. It contains reference material, practical tools, case studies, webinars and archived forums.