Executive Summary

Systematic and participatory hygiene promotion campaigns are vital to safeguard refugees and Internally Displaced People (IDPs) against water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)-related diseases. In rural settings, the goal is to provide a structure to promote hygiene that can reach all refugees and IDPs and can be compatible with the host communities’ social structures and infrastructure. The hygiene promotion strategies should be able to be sustained in the long-term and over a dispersed area. In addition, the goal is to obtain access for refugees and IDPs to national services, in order to enable them to practise proper hygiene and to maintain their health. The often-weak water and sanitation infrastructure in rural settings means that coordination and collaboration is fundamental to identify infrastructural gaps and to upgrade facilities as necessary to allow for successful hygiene promotion intervention. Communication strategies should use approaches that can get maximum coverage (posters, house visits) given that electronic media is often not widespread. Community mobilisation and participatory approaches can help to strengthen capabilities of both the affected refugee / IDP population and the rural host community. This factsheet details the relevant components of a hygiene promotion campaign and explains the relevant working steps for implementation, monitoring and ongoing assessment.

Introduction

Systematic and participatory planning approaches are needed to implement effective hygiene promotion campaigns for refugees and Internally Displaced People (IDPs) and their host communities (THE SPHERE PROJECT 2011, UNHCR 2015a). They promote positive behavioural change around household, food and personal hygiene and can facilitate meeting the Sphere Project Minimum Standards (UNHCR 2015a, THE SPHERE PROJECT 2011, GWC 2009). Careful planning, execution, monitoring and evaluation of hygiene promotion campaigns ensures that the affected populations have the knowledge, resources, willingness and practice to prevent WASH-related disease transmission of concern in Rural Settings (HARVEY 2015, WHO AND WEDC 2013).

Addressing the Rural Setting

The Challenge for Promoting Hygiene in Rural Settings

In rural areas, the infrastructure is often weak, which makes hygiene promotion particularly important to reduce risks of hygiene-related and waterborne diseases (UNHCR 2015a). Here, risky hygiene practices such as open defecation are more common than in other settings (e.g. Camps or urban areas) (UNICEF 2012a). Additionally, there are often large disparities in the level of WASH services across rural areas and access to them is often limited. This makes it difficult to consistently meet minimum standards for hygiene and makes the logistic of doing so challenging (e.g. ensuring soap and refuse receptacles are available, UNICEF 2012a, UNICEF 2012b).

On the other hand, rural settings often have direct access to local markets, which means that hygiene items can be made available to the affected population through local businesses, hence allowing them to take ownership for maintaining good hygiene. In this case, humanitarian actors must ensure that the affected communities are provided with the financial means (e.g. multipurpose grants, cash grants) to pay for their hygiene items and water, as the IDPs and refugees may otherwise be forced to ration their water use and hygiene items (UNHCR 2012b).

Families living at a rural site in Zahrani received non-food items from the international office from migration. Source: IOM (2013).

Coordination and Collaboration

The primary goal of WASH interventions in rural settings is to provide access to national hygiene-related services (such as health services, nutrition planning strategies and policies, programs for hygiene promotion, etc.) and to improve services if necessary (THE SPHERE PROJECT 2011, UNICEF 2012b, UNHCR 2015a). To provide access, it is vital that humanitarian actors, local stakeholders and service providers collaborate from the start and plan the campaign in a way that local stakeholders can take over with time to ensure sustainability of the campaign (UNHCR 2015a).

A young girl receives hygiene promotion material in a host community. Source: UNICEF JORDAN (2013).

Communication Strategies

In rural settings, the use of electronic mass media for hygiene promotion is often not very effective, since large parts of the population may not have access to televisions, radios or smartphones. Thus, posters and interactive methods such as home visits or group discussions are often more appropriate to disseminate and communication strategies (WHO AND WEDC 2013) (see Creating Information Material (DC) factsheet).

Schools can be another useful avenue for hygiene promotion in rural areas, since children can be very effective in disseminating information to their families (see CHAST approach). Teachers should, if possible, be integrated into hygiene promotion training programs (UNICEF 2014, see Recruiting and Training of Hygiene Promotion Facilitators factsheet).

If possible, hygiene promotion should apply an interactive approach, using methodologies such as drama, group discussions, songs, street theatre, or dance. In addition, WASH personnel should conduct house visits to make sure that any obstacles (such as language issues) are tackled to enable good communication. These communication methods can be adopted in public places such as markets, schools, distribution centres, worship places, water collection points or surroundings of sanitation facilities (HARVEY ET AL 2002). For any communication method selected, an assessment of the cultural norms of the refugee/IDP population and host communities must be carried out.

Communication and Participation

Having communities participate in hygiene promotion will allow humanitarian actors to gain a good understanding of how the public health can best be protected. Community mobilisation can then be used to empower communities to take ownership over maintaining good hygiene practices. Programmes for promoting hygiene awareness should be participatory, focused and specific, but not alarmist (WHO 2002). In rural areas, where ties of kinship are stronger than in urban areas, community leaders can have a strong influence on the community. They should thus be involved in hygiene promotion whenever possible (WHO 2002). Smaller neighbourhoods or groups that are geographically close to one another can be jointly mobilised to promote hygiene. This is a particularly appropriate strategy for populations dispersed over large areas and difficult for humanitarian actors to reach and conduct intensive hygiene promotion campaigns (HARVEY 2015).

Hygiene Committee or Health Clubs

If possible, WASH programs should have hygiene committees or health clubs developed and run in cooperation with the refugee and IDP population and the host community (UNHCR 2015a). All programs should have a gender-balanced and representative committee responsible for promoting hygiene and implementing hygiene promotion campaigns. In rural settings, Community-Led Total Sanitation and Participatory Hygiene and Sanitation Transformation (PHAST) are good approaches to community mobilisation (UNICEF 2012b).

Planning and Preparation – A Phased Approach

Mobilising the community for hygiene promotion is best done in a phased approach that is adapted to the level of development of rural areas and to the stage of the emergency/humanitarian crisis (HARVEY AND CONOLI 2015). In the immediate emergency phase, hygiene promotion should focus on (HARVEY AND CONOLI 2015):

- Ensuring necessary resources are provided to the refugee/IDP population to carry out proper hygiene.

- Ensuring that the refugee/IDP population has the basic knowledge to prevent disease.

- Mobilising the community to act to address WASH-related problems.

- Mobilising the community to act concerning the design, use, management of WASH services.

In the medium- to long-term post-emergency phase, hygiene promotion should follow an approach more in line with development settings, involving continuous assessment, analysis, design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of risks (a concept commonly referred to as Linking Relief, Rehabilitation and Development LRRD) (HARVEY 2015).

Steps in Hygiene Promotion Campaigning

Defining the Campaign Strategy

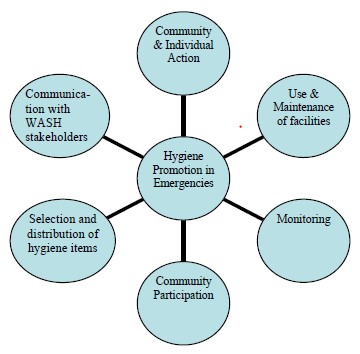

A strategy needs to be put in place that justifies ‘‘WHY hygiene promotion is important in the specific context, HOW the key hygiene risk practices have been identified, WHO are the priority at-risk groups and WHY, WHAT are the most effective hygiene promotion approaches and activities and WHY, HOW the target activities for each at-risk group will carry out and HOW the effectiveness of the plan will be monitored’’ (HARVEY 2015). The following components should be addressed by the strategy and prioritised according to the risk assessment: community and individual action, use and maintenance of facilities, selection and distribution of hygiene items, monitoring, community participation and communication with WASH stakeholders (see graph below).

Components of a hygiene promotion campaign. Source: GWC (2009).

Planning and Preparation

When planning a campaign, a team which is responsible for planning and executing the hygiene promotion campaign needs to be rapidly set up (WHO 2015). The assessment and preparation steps for developing a hygiene promotion campaign should be applied according to the following steps (adapted from GWC 2009, UNHCR 2015a, and HARVEY 2015):

Step 1: Assessment (see also factsheet on WASH Needs Assessment)

- Identify key risk practices and get an idea of the level of knowledge, the practices and level of understanding of WASH.

- Participatory approaches such as Participatory Rural Appraisals and problem tree analysis may allow members of the refugee and IDP community as well as the rural host community to analyse the situation related to hygiene and make their own decisions.

- Determine which practices allow for diarrhoeal microbes or diseases transmission.

- Identify the practices that are the most harmful to human health.

Step 2: Consultation

- As soon as possible, consult men, women and children on hygiene needs and items to include in hygiene kits.Seek to form a close liaison with the host community.

- It is necessary to separately assess the needs of refugee and IDP population residing with host families and those refugees congregating in public areas or land (HARVEY and COLONI 2015).

Step 3: Initial planning through definition of goals and objectives

- Define the aim of the entire campaign based on unique needs that were revealed in the needs assessment (see WASH Needs Assessment factsheet).

- Set one or two purpose objectives referring to the wider objectives of the campaign and targeting specific hygiene practices. Select these based on which practices have the greatest potential impact on public health and which are achievable. Also, consider what can be done to enable change of risk practices.

- Determine two to four outputs that should be achieved.

- Select measurable indicators and means of verification for each objective (such as those in Sphere Project Hygiene Promotion).

- Identify potential areas for intervention (e.g. on the hardware side such as water systems or hygiene items, or on the software side such as education or advocacy).

- Set out action plans for achieving the objectives.

Step 4: Planning through identifying target audiences and stakeholders

- Decide on which segments of the refugee/IDP population will be targeted by the campaign, based on an assessment of risky hygiene practices;

- Determine important stakeholders who influence the people that employ these risky practices (teacher, community leaders, etc.).

Step 5: Planning communication campaigns and modes of intervention

- Decide on initial key messages (such as WHO`s Facts for Life).

- Key messages should be provided early and should be in local languages and should consider levels of literacy. Keep in mind that literacy may vary largely in rural settings.

- Messages should target risk practices and not be communicated along with too many other messages.

- Posters and interactive methods such as home visits are often most appropriate as is the use of electronic mass media is often not very effective in rural settings (WHO AND WEDC 2013).

- Define the initial mode of intervention for media campaigns (see Media Campaigns - Radio (DC) and Creating Information Material (DC) factsheets) as well as for other means that the target audiences trust (women`s discussion groups, traditional healer). Also, define locations where to best reach target groups (consider gender).

- Determine advocacy and training needs for stakeholders (see Recruiting and Training of Hygiene Promotion Facilitators factsheet).

Step 6: Recruitment, identification and training of workers and outreach system

- Base recruitment and training on the capacities (systems, skills and approaches) that already exist among the active humanitarian actors (See Recruiting and Training of Hygiene Promotion Facilitators factsheet). In a rural setting, this should also include strengthening local capacities (e.g. municipal authorities and municipal and local services).

Implementation and Continued Assessment (see also Project Implementation factsheet)

- Implement the defined actions (e.g. distribution of hygiene kits or carrying out media campaigns).

- Hold meetings/ interviews with key informants and stakeholders to initiate an interactive approach.

- Conduct ongoing assessments to understand the motivation factors behind positive behavioural change around hygiene.

- Obtain quantitative data and carry out a systematic data collection in a participatory manner and in coordination with other sectors.

Monitoring (see also Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation factsheet)

- Monitor the hygiene promotion activities (e.g. distribution of hygiene kits, installation of toilets) and people’s level of satisfaction.

- Monitor and evaluate hygiene promotion campaigns against hygiene-related indicators on safe access to quality sanitation and on satisfactory living conditions (UNHCR 2015b). The relevant indicators for rural settings (referred to in standard as “out of camp setting”) include:

- ≥ 90% of households have soap present in the house (which can be presented within 1 minute),

- ≥ 60% (emergency stage)/ 80% (post emergency stage) of households can name 3 of the 5 circumstances in which it is critical to wash hands

Adaptation

- Refine the campaign based on the changing situation and move towards more interactive methods of communication and participation in comparison towards later emergency stages.

- Rapidly adapt the intervention and campaign based on monitoring outcomes and empower the communities to maintain their longer-term hygiene promotion structure (e.g. committees).

- Continue training and monitoring and adapt approaches as necessary.

Planning Timelines

Hygiene promotion plans should be revised every six months based on monitoring outcomes (HARVEY 2015).

Promoting the Maintenance of Good Hygiene Practices in the Long-term

To ensure that the hygiene promotion campaign promotes practices that can be sustained in the long-term, the following points should be considered (IA 2014):

- Use multiple communication methods and make use of hygiene promoters, schools, women’s groups, youth groups and mass media;

- Carry out multi-sector planning and delivery together with health, child protection, livelihoods and non-food items sectors;

- Increase participation and decision making of beneficiaries;

- Use a child-centred approach (see CHAST approach);

- Approach disease monitoring and awareness campaign in an integrated health and education manner;

- Support and strengthen WASH committees and health clubs;

- Monitor and conduct impact assessment and use the information gathered in programme planning and adapting hygiene promotion campaigns.

- Ensure systems are in place for operation and maintenance of facilities to enable maintaining good hygiene practices (see Ensuring Appropriate Operations and Maintenance Services factsheet).

Applicability

The guidance is applicable to a rural setting with refugees and IDPs living in individual accommodation, within host families or on public land in rural areas.

Hygiene Promotion in Emergencies

This Global Wash cluster manual provides training materials and handouts for facilitators to train hygiene prompters. It contains advice on hygiene promotion related non-food items selection and delivery. The WASH related non-food items briefing paper addresses maximizing benefits of the distribution of hygiene items, selection of hygiene items, guidance on distribution and tips for improving distribution of items, as well as suggestions for improved coordination.

GWC (2009): Hygiene Promotion in Emergencies. A Briefing Paper. New York: Global WASH Cluster URL [Accessed: 08.11.2016]UNHCR WASH Manual

This briefing paper provides basic information on Oxfam`s hygiene kits. It introduces the types of hygiene practices that are enable through the items in the kits and prices details on the contents of Oxfam’s basic hygiene kit.

HARVEY, B. (2015): UNHCR WASH Manual. Geneva: United High Commission for Refugees URL [Accessed: 09.11.2016]Approaches to WASH Service Provision for Urban Refugees

Emergency Sanitation: Assessment and Programme Design

This book has been written to help all those involved in planning and implementing emergency sanitation programmes. The main focus is a systematic and structured approach to assessment and programme design. There is a strong emphasis on socio-cultural issues and community participation throughout.Includes an extensive “guidelines” section with rapid assessment instructions and details on programme design, planning and implementation.

HARVEY, P. BAGHRI, S. REED, B. (2002): Emergency Sanitation: Assessment and Programme Design. Loughborough: Water, Engineering and Development Centre (WEDC) URL [Accessed: 31.05.2019]WASH strategy for 2014

Families living at a rural site in Zahrani received non-food items from the International Office for Migration

Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response

The Sphere Project is an initiative to determine and promote standards by which the global community responds to the plight of people affected by desasters. This handbook contains a humanitarian charter, protection principles and core standards in four disciplines: Water, sanitation and hygiene; food security and nutrition; shelter, settlements and non-food items; and health action.

THE SPHERE PROJECT (2011): Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response. Bourton on Dunsmore: Practcal Action Publishing URL [Accessed: 31.05.2019]WASH in Rural Areas

This entry discusses WASH responses in rural dispersed settings. WASH interventions help to improve hygiene and health, and reduce morbidity and mortality among both refugees and host populations. In the first phases of an emergency, a WASH response in rural dispersed settings focuses on identifying WASH infrastructural gaps and needs, and software components required, as well as monitoring the WASH situation.

UNHCR (2015): WASH in Rural Areas. In: UNHCR ; (2015): Emergency Handbook. Geneva: . URL [Accessed: 26.10.2016]Emergency Hygiene Standard

Communication Strategy on Water, Sanitation & Hygiene for Diarrhoea and Cholera Prevention

UNICEF work in Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) in Humanitarian Action 2012

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene, Annual Report 2013

Syrian Bi-Weekly Humanitarian Situation Report. June 28-July 11: Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Turkey

A young girl receives hygiene promotion material in a host community in Jordan

Chapter 15: Health promotion and community participation

This chapter of the book presents guidance for managing disaster caused emergencies related to communicating participation, health promotion, health education, and hygiene promotion. The chapter addresses hygiene promotion and community participation in difference stages of the disaster management cycle. The chapter also provides guidance on community participation with respect to the opportunities and needs for community participation, hygiene promotion principles of community participation, obstacles to community participation, and techniques to overcome obstacles and reaching the community as well as community organization in rural and urban areas. Hygiene promotion and hygiene education are also address by address the perception of risk and awareness raising, the need for hygiene promotion in emergencies, steps to setting up a programme for hygiene promotion, participatory approaches to hygiene promotion, environmentally health messages in emergencies as well as communication methods.

WHO (2002): Chapter 15: Health promotion and community participation. In: WISNER, B. ; ADAMS, J. ; (2002): Environmental Health in Emergencies and Disasters. A Practical Guide. Geneva: . URL [Accessed: 12.12.2016]Hygiene promotion in emergencies

This guidance document is for managers of WASH programs to manage their hygiene promotion campaigns programmes. This clear and well-presented guidance document provides background information for hygiene, hygiene practices in camps, and the F-diagram. It also concisely summarises types of evaluation and monitoring. It presents pertinent information on principles of hygiene promotion, selection and training facilitators, methods of hygiene and sanitation promotion, planning guidance for hygiene promotion campaign and method of implementing a plan of action. Further guidance is provided on how to analyse assessment information and available participatory tools that may be used.

WHO WEDC (2011): Hygiene promotion in emergencies. In: WHO ; WEDC ; (2011): Technical Notes on Drinking-Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Emergencies. Geneva: . URL [Accessed: 04.11.2016]Gap Analysis in Emergency Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion

This is a gap analysis report which analyses emergencies situations to identify over 50 programming gaps in the areas of water, sanitation and hygiene. The most hygiene promotion related significant gaps included the importance of understanding the context and weak community participation.

BASTABLE, A. RUSSEL, L. (2013): Gap Analysis in Emergency Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion. Oxford: Humanitarian Innovation Fund URL [Accessed: 08.11.2016]Introduction to Hygiene Promotion: Tools and Approaches

This is a manual with training material and handouts for facilitators to prepare training for hygiene promotion at different levels. The manual provides hygiene promotion training materials including tools and approaches for training including human resources planning, recruitment, and management, WASH generic job description for hygiene Promotion staff and volunteers, and a list of essential hygiene promotion equipment for communication.

GWC (2009): Introduction to Hygiene Promotion: Tools and Approaches. Geneva: Global WASH Cluster URL [Accessed: 08.11.2016]Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Emergencies

The International Red Cross’s Health Guide Book provides a chapter providing guidance to improving water, sanitation, hygiene and vector control in emergency settings. It provides information on assessing needs in different phases, identifying the vulnerable group, and determine diseases to target. It provides guidance on disease transmission, community involvement in disease prevention with detail on the requirement in early emergencies phases.

JOHN HOPKINS UNIVERSITY IFRC (2008): Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Emergencies. Baltimore: John Hopkins University URL [Accessed: 14.11.2016]A Review of Evidence-based for WASH Interventions in Emergency Response/Relief Operations

This review discusses evidence on different approaches to Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene interventions contrasting the development context to the emergency content. Using reviews of cases, the report discusses the types of hygiene promotion interventions commonly applied and the approaches commonly applied. The report details the shift towards trend towards integrated approaches to after, sanitation, and hygiene. Requirements for effective hygiene promotion in emergencies are explored for different approaches to hygiene promotion as well as programming and implementation issues.

PARKINSON, J. (2009): A Review of Evidence-based for WASH Interventions in Emergency Response/Relief Operations. London: Atkins URL [Accessed: 14.11.2016]Chapter 15: Health promotion and community participation

This chapter of the book presents guidance for managing disaster caused emergencies related to communicating participation, health promotion, health education, and hygiene promotion. The chapter addresses hygiene promotion and community participation in difference stages of the disaster management cycle. The chapter also provides guidance on community participation with respect to the opportunities and needs for community participation, hygiene promotion principles of community participation, obstacles to community participation, and techniques to overcome obstacles and reaching the community as well as community organization in rural and urban areas. Hygiene promotion and hygiene education are also address by address the perception of risk and awareness raising, the need for hygiene promotion in emergencies, steps to setting up a programme for hygiene promotion, participatory approaches to hygiene promotion, environmentally health messages in emergencies as well as communication methods.

WHO (2002): Chapter 15: Health promotion and community participation. In: WISNER, B. ; ADAMS, J. ; (2002): Environmental Health in Emergencies and Disasters. A Practical Guide. Geneva: . URL [Accessed: 12.12.2016]Chapter 15: Health promotion and community participation

The Inter-Agency Nutrition Committees conducted a situation analysis and vulnerability assessment of Syria refugees in terms of conditions in Lebanon. They found that in rural areas there was a lack of basic sanitation and hygiene conditions were poor. The gaps identified included that hygiene promotion activities were implemented in a very limited manner and often in one-off promotion sessions and there was a lack of a coherent and systematic approach.

WHO (2002): Chapter 15: Health promotion and community participation. In: WISNER, B. ; ADAMS, J. ; (2002): Environmental Health in Emergencies and Disasters. A Practical Guide. Geneva: . URL [Accessed: 12.12.2016]Introduction to Hygiene Promotion: Tools and Approaches

This is a manual with training material and handouts for facilitators to prepare training for hygiene promotion at different levels. The manual provides hygiene promotion training materials including tools and approaches for training including human resources planning, recruitment, and management, WASH generic job description for hygiene Promotion staff and volunteers, and a list of essential hygiene promotion equipment for communication.

GWC (2009): Introduction to Hygiene Promotion: Tools and Approaches. Geneva: Global WASH Cluster URL [Accessed: 08.11.2016]twine.unhcr.org/app/

The UNHCR provides a streamlined global health information toolkit, TWINE. It contains report for prospective health surveillance that monitors access in urban areas to health facilities, a WASH report cards, a disease outbreak report cards, a food assistance report card, and a SENSE nutrition survey database.

ceecis.org/washtraining/index.html

This WASH sector visual aid library was collected from numerous sources with pictures, example leaflets, posters, graphics, visual aids, and interactive exercises to promote safe hygiene practices. Example radio spots and videos are also provided.

www.ben-harvey.org/UNHCR/WASH-Manual/Wiki/index.php/Chapter_8

An online handbook by Ben Harvey provides UNHCR guidance on the importance of hygiene promotion, priority actions, and approaches in refugee settings. Guidance is also provided for preparing a strategic hygiene plan and global tools, use of hygiene promotion training materials and annexes with key references.

emergency.unhcr.org/entry/33096/emergency-hygiene-standard

The UNHCR handbook provides an emergency hygiene standard. An annexe is provided relevant reading further information including hygiene promotion global Strategies, the Sphere handbook, and UNHCR indicators.

watsanmissionassistant.wikispaces.com/Software+hygiene+promotion

IRFC International Water and Sanitation Centres provide a hygiene information box online with key reports, information communication instruction for specific regions, and hygiene promotion communication material for specific regions. It also includes training modules and links to further resources relevant for hygiene promotion software for emergencies.

washcluster.net/tools-and-resources/

The website provides tools and resources from the Global WASH Cluster to support the build-up and during emergency response phases. It provides resources for assessment, coordination, information management, WASH Technical, WASH Training, as well as cross-cutting issues, inter-cluster, and transformative agendas. The resources for the hygiene promotion specific tools and approaches are accessible over this platform.