Executive Summary

The term camp refers to a form of settlement in which refugees or Internally Displaced People (IDPs) reside and receive protection, humanitarian assistance and other services from host governments and humanitarian actors (UNHCR 2015a). A camp's location, size, design and duration are context-specific. Usually, a national or international non-governmental organisation or a national authority assumes the responsibility for the camp management. This factsheet describes the different types of camps, including reception and transit centres, collective centres, planned camps and self-settled camps.

Introduction

Definition and Characteristics of Camps

Reception and Transfer Centres

Collective Centres

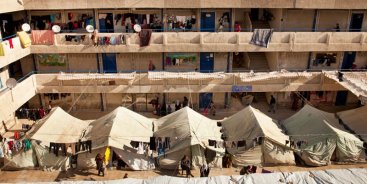

Al-Rameh collective shelter, Jaramana, Syria. Source: C. ALFARAH/UNRWA (2013), taken from UNRWA (2016)

Planned Camps

Trying to build a planned refugee camp in Jordan (Azraq refugee camp). Source: ADAYLEH R. (2015) taken from ASSOCIATED PRESS (2015)

Self-settled Camps

Refugees from Kosovo settle spontaneously in a makeshift camp in the no man’s land at border between Macedonia and Kosovo, near Blace. Source: H. J. DAVIES/UNHCR (1999), taken from COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (2011) .

Self-settled camps are created spontaneously when displaced communities, often smaller family groups, settle on state-owned, private or communal land, that has not been allocated or designated to accommodate them. They tend to be established prior the arrival of humanitarian organisations, that may advise the local authorities on whether the site and settlement can be supported and improved, or whether alternative settlement options need to be developed. However, in most cases, there is limited or no negotiation with the local population or private land owners over the use and access to the land, and as a result they remain independent of assistance and without receiving any humanitarian intervention (adapted from IOM, NRC AND UNHCR 2015, DFID et al 2008 and UNHCR 2015a). This often creates a conflict-ridden environment, and the provision of services may become cumbersome and costly (UNHCR 2015a).

Trying to build a planned refugee camp in Jordan (Azraq refugee camp)

Al-Rameh collective shelter, Jaramana, Syria

A year on, 'model' camp for Syrian refugees has mixed record

CCCM Cluster. In: About Us. Providing Equitable Access to Services.

Only genuine justice can ensure durable peace in the Balkans

Camp Management Toolkit

International Organisation for Migration (IOM), Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR)`s Camp Management Toolkit provide tools and approaches to provide concrete guidance on facilitating hygiene improvement in an acute, early stage of an emergency relevant to camps. This toolkit is applicable to both IDPs and refugees living in communal settings.

IOM NHCR UNHCR (2015): Camp Management Toolkit. Genva: International Organization For Migration URL [Accessed: 25.08.2016]Refugees from Kosovo settle spontaneously in a makeshift camp in the no man’s land at border between Macedonia and Kosovo, near Blace.

Transitional Settlement and Reconstruction after Natural Disasters, Field Edition

FMO Thematic Guide: Camps Versus Settlements. Forced Migration Online

Resource for Speakers on Global Issues. Refugees: The Numbers

Policy on Alternatives to Camps

This document describes the UNHCR Policy on alternatives to camp, enforced since July 22, 2014. UNHCR’s policy is to pursue alternatives to camps, whenever possible, while ensuring that refugees are protected and assisted effectively and are able to achieve solutions. The policy is directed primarily towards UNHCR staff members and those responsible for the development of protection, programme and technical policies, standards, guidance, tools and training that support such activities.

UNHCR (2014): Policy on Alternatives to Camps. Geneva: United Nations High Commission for Refugees URL [Accessed: 14.07.2016]Spontaneous Settlement Strategy Guidance. In: Emergency Handbook.

Site Planning for Transit Centre. In: Emergency Handbook.

Camp Planning Standards (Planned Settlement). In: Emergency Handbook

Collective Centre Strategy Considerations. In: Emergency Handbook

Shelter Design Catalogue

Into the cold in Syria

Transitional Settlement and Reconstruction after Natural Disasters, Field Edition

Emergency Handbook

The UNHCR Emergency Handbook is the 4th edition of UNHCR’s Handbook for Emergencies, first published in 1982. This digital edition is primarily a tool for UNHCR emergency operations and its workforce. It contains entries structured along seven main topic areas: Getting Ready, Protecting and Empowering, Delivering the Response, Leading and Coordinating, Staff Well-Being, Security and Media.

UNHCR (2015): Emergency Handbook. Geneva: United Nations High Commission for Refugees URL [Accessed: 16.08.2016]Camp Management Toolkit

International Organisation for Migration (IOM), Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR)`s Camp Management Toolkit provide tools and approaches to provide concrete guidance on facilitating hygiene improvement in an acute, early stage of an emergency relevant to camps. This toolkit is applicable to both IDPs and refugees living in communal settings.

IOM NHCR UNHCR (2015): Camp Management Toolkit. Genva: International Organization For Migration URL [Accessed: 25.08.2016]South Sudan: A Nation Uprooted. Refugees International: Field Report

This field report presents the situation of refugees and IDPs in Sudan, caused by the conflict which erupted in South Sudan’s capital, Juba, in December 2013, where thousands of civilians were targeted and killed. As of February 2015, the number of South Sudanese thought to be displaced by the conflict had reached 2 million, including 1.5 million internally displaced people (IDPs) and roughly 500,000 refugees living in Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and Sudan.

BOYCE, M YARNELL, M. (2015): South Sudan: A Nation Uprooted. Refugees International: Field Report. Washington: Refugees International URL [Accessed: 29.08.2016]Jordan – Azraq Camp Factsheet

This factsheet provides key information of the Azraq Camp opened in 2014.

UNHCR (2016): Jordan – Azraq Camp Factsheet . Geneva: The United Nations High Commission for Refugees URL [Accessed: 29.08.2016]https://emergency.unhcr.org

The UNHCR Emergency Handbook is the 4th edition of UNHCR’s Handbook for Emergencies, first published in 1982. This digital edition is primarily a tool for UNHCR emergency operations and its workforce. It contains entries structured along seven main topic areas: Getting ready, Protecting and empowering, Delivering the response, Leading and coordinating, Staff well-being, Security and Media.

www.unhcr.org

This is the official web site of the UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, containing key and up-to date information about the status of refugees worldwide, as well as multiple publications and resources.

http://internationalrelations.org/a-guide-to-understanding-refugee-camps/

“A guide to understand camps” presents different types of refugee camps, how refugee camps work, how many refugee camps exist, as well as a host of other issues.

www.unocha.org

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is the part of the United Nations Secretariat responsible for bringing together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies. OCHA also ensures there is a framework within which each actor can contribute to the overall response effor