المُلخص التنفيذي

“Public sector utilities in developing countries have often not been efficient in providing access to reliable water and sanitation services. [...] Countries across the world are increasingly looking to the private sector for help in providing needed water services. Towards this end, privatisation of water and sanitation services is viewed to be a cost effective method of service delivery that also enhances quality and performance” (NYANGENA 2008). However, the privatisation of former publicly owned sectors or utilities always raises concerns. In cases of privatising the water and sanitation sector of a town, community or even a whole country causes more than only concerns – it raises fierce protests and sometimes even violent opposition (QUEHENBERGER 2008). Focussing on benefits and challenges of privatisation in sanitation and water management, we will define actors and models of the tool, and lead through four implementation stages to ensure a smooth change to privatisation on the local level.

Introduction

Private sector participation in form of privatisation is one option when building an institutional framework for sanitation and water management (see building an institutional framework for more information on building an institutional framework for sanitation and water management, which might help to get an overview of what else can be done). In general, sanitation and water management can be in public hands (see nationalisation), or in private hands ― which will be discussed below ― or it is a mixture of both, like with public private partnerships (adapted from THE WORLD BANK 2006).

Problems in Water and Sanitation Services

(Adapted from THE WORLD BANK 2006)

“In many developing countries, the delivery of water services is unsatisfactory. Many households do not receive water from the main utility, even though they would be prepared to pay for the service. Others are connected, but get water for only a few hours a day. Even fewer are connected to a sewer network. Often the water is not safe to drink and the wastewater is not properly treated” (THE WORLD BANK 2006). The most serious obstacles ― under both public and private operation ― to achieving a local government’s goals in water and sanitation management are:

- Water and sanitation services are critical to all consumers.

- They are often provided under conditions of natural monopoly; one well-run firm can supply the services at a lower cost than two or more well-run firms.

- The investments required to provide the services are often long-lived and irreversible; once made, they cannot be reversed should the returns to the investment prove less than expected.

The biggest challenge for local governments is to address these problems and thus encourage investments to improve quality, lower costs, and extend access. One possibility to do so might be the privatisation of parts (or all parts) of the sanitation and water management sector.

Possible (Positive) Effects of Privatisation

(Adapted from THE WORLD BANK 2006)

Privatisation introduces an operator that is independent of the local government and has a strong incentive to be profitable. For the local government, this might cause some problems, as a private provider can not be directed in the same way as a public provider, and might have the incentive to take actions that are not in the public interest but enable more profits. Yet, independence and incentive to profits may also help the local government to achieve its objectives. Effects can mostly be seen in three areas:

- Operating performance: The profit incentive might motivate the private provider to operate more efficiently than its public counterpart.

- Investment decisions: The profit incentive might lead the private operator to make deliberate investments decisions and miss fewer profitable opportunities to expand the business, e.g. extending access to unconnected households that want service and can pay for it.

- Policy and its enforcement: The presence of independent private providers might lead to governmental problems like trading policy for money, as the private provider might try to shape those policies and pays for it with services and money. For this reason, good arrangements and deliberate policies and enforcement methods need to be in place (see also political and legal framework or strengthening enforcement bodies.)

The private sector has always been involved in the water and sanitation sector in some form or other, from tendering for construction contracts in large urban supplies to the informal provision of vended water in unserved areas. However, a new role is currently being shaped due to globalisation and the importance of private participation in the water and sanitation sector is increasing (INWRDAM 2010).

Problems of Privatisation

Even though privatisation is likely to be seen as a way to solve the problem of poor governmental capacity to deliver water and sanitation service, there are often also problems with private sector participation that need to be considered. GREEN (2003) brings forward four main problems:

- Undermining capacity: Private sector participation often undermines local (and national) government capacity, which leads to limited capacity of governments to take services back into their management when contracts end or fail. Privatisation should not result in increased or irreversible dependence on private companies, and there must be clauses in the contract to prevent this dependence.

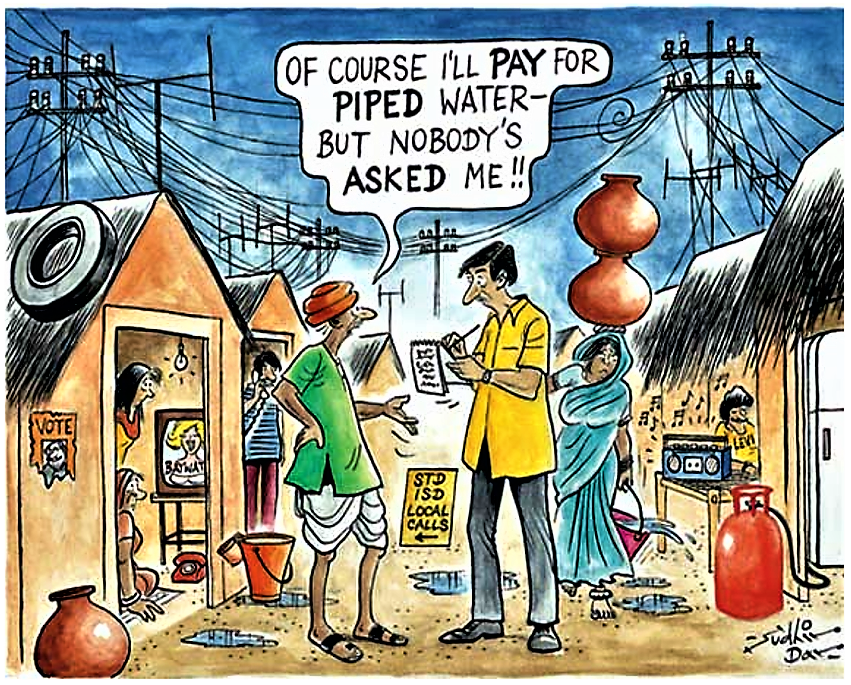

- Poor people as recipients rather then participants: The involvement of local communities and users of water and sanitation services is often lacking in private sector involvement reform programmes. Poor people are still mainly seen as recipients rather than contributors to development. Whether the contracts involve large-scale or small-scale private sector participation, the focus is on giving contracts to the private sector for constructing or operating services. Urban and rural communities are rarely consulted, leading to a lack of ownership. It would seem that old problems such as lack of community involvement, which led to previous failures, are continuing, raising serious doubts over the sustainability of privatisation projects.

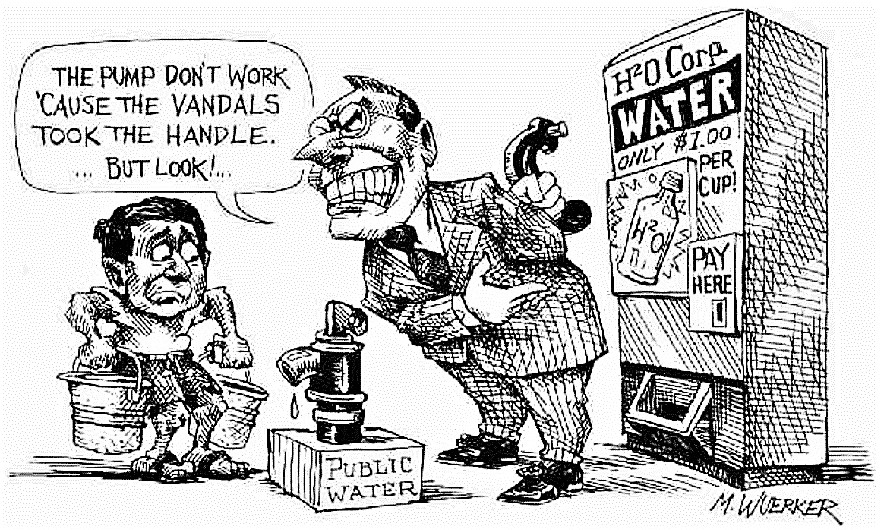

- Inflexible finances: Cost recovery and capital cost contributions are necessary if water services are to be made sustainable over time. However, the way these principles are applied often denies poor people access to services. Expensive technology choices and a failure to consider non-cash contribution the poor are able to make are widespread amongst those involved in private sector participation contracting. Donors are guilty of promoting an approach that is narrow and mechanistic, allowing for little flexibility and wider perspectives incorporating community action and the complexities of poverty.

- Compromised accountability: Decentralisation has not seen the benefits of responsiveness to people’s needs and greater accountability in many countries. Often, this is because the central governments have not increased the local government’s personnel or trained them to manage greater responsibility. Weak decentralised government agencies can not be expected to learn quickly about private sector contracting and be able to monitor and supervise the activities of contractors beyond provincial capitals. Therefore, decentralisation needs to be a well prepared process to enable the local governments to cope with privatisation (see also decentralisation).

In addition to this, the following problems might appear and need to be considered when the private sector gets involved in sanitation and water management:

- In some cases the water prices/tariffs for the civil society have risen due to the privatisation (adapted from ARDHIANIE 2005)

- The private investor might only be interested in profitable cities, and not in rural, poor areas.

- Protest and fear of the civil society might lead to conflicts. Therefore, the involvement of the community in the process is necessary, with an opportunity to comment on proposals through, for example, commenting on tender documents and the planning and design of contracts, so that reforms will further the concerns of poor people. Proactive openness and transparency by the local government in all reform processes will also lessen the possibility of civil strife.

- Operation and maintenance might be forgotten by the private investor after successful implementation of new utilities

Actors of Privatisation

(Adapted from GREEN 2003)

There might be many stakeholders involved in privatisation, some of them may be based outside the country. Below is a list of possible stakeholders:

- Commercial banks provide loans for private companies. Their loans tend to be more expensive than loans from other sources, which increases the cost of a project.

- International financing institutions include for instance the World Bank, the International Monetary Found or other international development bank. Along with donors, they might make loans to the local government.

- Donors include multi-lateral donors like the European Union, the World Bank, or other development banks. They also include bilateral donors, which are official aid agencies in developed countries. International financing institutions and donors might force governments to privatise by putting a condition on funding.

- The government authority (central, local, municipal) is the client. It is in control of the project and so is the decision-maker, but will face lots of pressure from different stakeholders.

- Consultants include lawyers, staff of private companies like engineers and project managers or independent consultants. They are hired by the (local) government to bring in expertise on certain aspects of the privatisation.

- Private companies are involved in bidding for the contract. Companies expressing interest in the contract might include manufacturers, consultancy firms and construction and engineering companies. Many of these companies offer expressions of interest early on, with no intention of submitting a bit, in order to get commercial information on the water market.

- Other stakeholders might be directly or indirectly affected by or interested in privatisation, such as NGOs, Civil Society Organisations, environmentalists, lawyers, media, workers, academics, human rights advocates and Community-Based Organisations.

- The civil society needs to be included in the process for ensuring a smooth change process (and to avoid the risks of civil opposition).

Models of Privatisation

(Adapted from REES 2008)

Privatisation occurs with any introduction of private sector participation in the ownership and/or control (responsibility for day-to-day management) of a sanitation and/or water service institution. The more the private sector is involved in the ownership and control, the more private sector oriented is the model of privatisation. Below listed are the different models of privatisation:

- Service contract ― Buying in: Single function contracts to perform a specific service for a fee, e.g. instal meters.

- Management contract: Short-term contracts, typically for five years, where a private firm is only responsible for operations and maintenance.

- BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer)/ BOO (Build-Operate-Own): Contracts are issued for the construction of specific items of infrastructure, such as a bulk supply reservoir or treatment plant. Normally, the private sector is responsible for all capital investment and owns the assets until transferred to the public sector, but in BOO schemes, private ownership is retained.

- Lease: Long-term contract (usually 10-20 years but can be longer), after which the private sector is responsible for operations and maintenance and sometimes for asset renewals. Assets remain in public sector and major capital investment is a public responsibility.

- Concession: The local government lets a long-term contract, usually over 25 years, to a private company, which is responsible for all capital investment, operations and maintenance. The assets themselves remain public sector property.

- Partial divestiture: The local government sells a proportion of shares in a ‘corporatised’ enterprise or creates a new joint venture company with the private sector.

- Full divestiture: Full transfer of assets to private sector through asset sales, share sales or management buyout. Private sector responsible for all capital investment, maintenance, operations and revenue collection.

Take into consideration

(Adapted from THE WORLD BANK 2006)

Among things to be considered before privatising are:

- Consider possible positive and negative effects of privatisation on customers (higher costs, better connexion to water and sanitation facilities, etc.) and other stakeholders.

- Tariffs might change ― this needs to be worked out according to a proposed arrangement (see also water pricing).

- Choosing and designing good institutions for monitoring and enforcement of operator performance, adjusting tariffs and resolving disputes is important (see also participatory monitoring and enforcement).

- Arrangements need to be transparent ― they should be published and the operator should be selected in an open process.

- Roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders involved need to be clarified (contracts).

- Public support is better than protest: awareness raising (see PPT) is important to gain public support and to avoid the fear of ‘losing’ a public good through privatisation, e.g. with media campaigns.

- The private provider needs to have the ability to make good operating and investment decisions and therefore have enough freedom. It should gain when making decisions right and loose when getting them wrong. “The provider should be allowed to do well when it improves the business, but likewise it should bear the risks it has agreed to bear; it should not automatically be able to renegotiate the agreement when its profits decline” (THE WORLD BANK 2006).

- Furthermore, the operator needs to be protected from the risk of local government changes or changes in the rules of the game, like cutting the prices after the operator has invested (THE WORLD BANK 2006).

Implementation of Privatisation

(Adapted from THE WORLD BANK 2006)

The preparation and implementation of an arrangement for privatisation usually involves four stages that might be overlapping and iterative:

Stage 1 ― Developing the policy: Objectives are set within this stage, and the reform leader needs to be identified. Ground rules for the structure of the sector are determined. Important sub-steps of stage 1 are:

- Allocating responsibilities to different tiers of local government, e.g. which level of local government should have the responsibility for water services?

- Deciding on the market structure:How should each provider’s service area be determined? Should a single provider have the responsibility “from source to tap” or should functions such as bulk supply be separated from distribution? Etc.

- Setting competition rules:The local government needs to consider questions whether to award exclusive franchises, whether to encourage alternative providers, whether to allow water operators to merge, etc.

Stage 2 ― Designing the details of the arrangement: Work on service standards and tariffs, risk and stakeholder views comes together to define the responsibilities the local government intends to assign to the operator and how the relationship will be managed. At the end of this stage, laws and contracts embodying the proposed arrangements may be drafted, and when necessary, bodies to implement the arrangement created.

Stage 3 ― Selecting the operator: The local government tries to attract potential operators, selecting the operator that offers the best combination of technical skills and cost to fit the local needs and circumstances.

Stage 4 ― Managing the arrangement: After the operator is selected, the hard work of managing the relationship starts. If the design stage was done well, the rules and institutions created should keep the relationship on track and serve the public interest. But, any new relationship of the magnitude and importance of private participation in sanitation and water management is likely to take some time to work smoothly, and special efforts will be needed to get the arrangement off to a good start. During all but the shortest and simplest of arrangements, there are likely to be tariff reviews and other adjustments. At the end of the initial contract period, the local government needs to decide on the next steps.

The time required for the four steps differs from region to region and by the arrangement proposed. In countries with laws supportive for privatisation in sanitation and water services and with good-quality information on the system the process might go on rapidly. Also, a management contract takes less time to prepare and implement than a concession. With strong commitment of the local government, a management contract might be designed and implemented in under 12 months, and a concession can easily require two years.

Securing the financing might need to be addressed separately from selecting the operator, e.g. with leases or management contracts.

Each stage of the arrangement requires a different level of detail and precision, so the local government should consider all different subject areas like financing, responsibilities, tariffs, etc. before deciding on a type of arrangement.

The applicability of privatisation differs from region to region and depends on the arrangement proposed. In countries with laws supportive for privatisation in sanitation and water services and with good-quality information on the system, the process might be very applicable.

Generally, privatisation is applicable in urban areas (including slums and informal settlements), small towns, and rural areas, as long as a serious private operator can be found.

Privatisation does not necessarily have to take over the whole sanitation and water management sector. Contracts can also be made for small, specific sectors (like with service or management contracts or BOTs or BOOs), so their applicability is good on a local level.

Privatisation is not appropriate in the case of projects which result in fast technological and other changes, as it would be difficult to determine in the long-term and with an acceptable level of certainty the standard of services rendered. The provision for a sufficient level of contractual flexibility is necessary to adapt to such rapid changes, and at the same time to foresee and agree in advance on the cost of such adjustments (APPP 2009).

A Step by Step Guide to Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

Water Privatisation in Indonesia

Advocacy Guide to Private Sector Involvement in Water Services

This guide is very helpful to plan of privatisation. It first gives some background information on privatisation, then discusses whether privatisation is a good solution and last leads through the actual planning and implementation.

GREEN (2003): Advocacy Guide to Private Sector Involvement in Water Services. London: WaterAid and Tearfund URL [Accessed: 15.04.2019]Public Private Partnership in Water and Sanitation Sector

Privatization of Water and Sanitation Services in Kenya: Challenges and Prospects

This document is about privatisation of water and sanitation services in Kenya. It includes some helpful recommendations after it describes the whole privatisation process with challenges and prospects in Kenya.

NYANGENA (2008): Privatization of Water and Sanitation Services in Kenya: Challenges and Prospects. Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa URL [Accessed: 02.09.2010]Contractual Design and Renegotiation in Water Privatisation

Regulation and Private Participation in the Water and Sanitation Sector

For getting good background information and detailed theoretical knowledge, this document might be best. It offers a very detailed and well structured insight in the topic and might therefore be helpful for a successful planning and implementation phase.

REES (2008): Regulation and Private Participation in the Water and Sanitation Sector. Stockholm: Global Water Partnership (GWP) URL [Accessed: 02.09.2010]Approaches to Private Participation in Water Services. A Toolkit

This toolkit by the World Bank leads through the whole planning and implementation phase. It offers both theoretical background material and practical guidelines for the process in a very detailed way, including stakeholder analysis and institutional and legal framework conditions.

THE WORLD BANK (2006): Approaches to Private Participation in Water Services. A Toolkit. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank URL [Accessed: 15.04.2019]WSP 2002 Cartoon Calendar

WSP 2000 Cartoon Calendar

Advocacy Guide to Private Sector Involvement in Water Services

This guide is very helpful to plan of privatisation. It first gives some background information on privatisation, then discusses whether privatisation is a good solution and last leads through the actual planning and implementation.

GREEN (2003): Advocacy Guide to Private Sector Involvement in Water Services. London: WaterAid and Tearfund URL [Accessed: 15.04.2019]Privatization Revisited: Lessons from Private Sector Participation in Water Supply and Sanitation in Developing Countries

This paper examines the experiences of private sector participation in the sanitation and water sector. It offers a theoretical overview of the topic.

GUNATILAKE CARANGAL-SAN JOSE (2008): Privatization Revisited: Lessons from Private Sector Participation in Water Supply and Sanitation in Developing Countries. Manduluyong City: Asian Development Bank URL [Accessed: 15.04.2019]Regulation and Private Participation in the Water and Sanitation Sector

For getting good background information and detailed theoretical knowledge, this document might be best. It offers a very detailed and well structured insight in the topic and might therefore be helpful for a successful planning and implementation phase.

REES (2008): Regulation and Private Participation in the Water and Sanitation Sector. Stockholm: Global Water Partnership (GWP) URL [Accessed: 02.09.2010]Approaches to Private Participation in Water Services. A Toolkit

This toolkit by the World Bank leads through the whole planning and implementation phase. It offers both theoretical background material and practical guidelines for the process in a very detailed way, including stakeholder analysis and institutional and legal framework conditions.

THE WORLD BANK (2006): Approaches to Private Participation in Water Services. A Toolkit. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank URL [Accessed: 15.04.2019]Tapping the Market - Opportunities for Domestic Investments in Water for the Poor

To improve access to safe water, particularly by the poor, developing country governments and the international development community are looking to the domestic private sector to play an expanded role. This report examines piped water schemes in rural areas of Bangladesh, Benin, and Cambodia and concludes that in the three study countries, un-served people could increasingly rely on service provision through the domestic private sector as the potential market the domestic private sector could be serving is very large.

THE WORLD BANK ; WSP ; IFC (2013): Tapping the Market - Opportunities for Domestic Investments in Water for the Poor. (= Conference Edition ). Washington: The World Bank, Water and Sanitation Program (wsp), International Finance Corporation (IFC) URL [Accessed: 05.09.2013]Reclaiming Public Water. Achievements, Struggles and Visions from Around the World

This publication takes a different perception and presents case studies on different forms of public water management — be they successful examples of publicly managed water provision or also cases where the public water provision needs to be improved. Furthermore, it also presents the struggle for people-centred public water and ways forward for improving public water services.

BALANYA, B. ; BRENNAN, B. ; HOEDEMAN, O. ; KISHIMOTO, S. (2005): Reclaiming Public Water. Achievements, Struggles and Visions from Around the World. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute (TNI) and Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) URL [Accessed: 27.10.2010]New Models for the Privatization of Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor

This paper draws on the authors’ experience working in informal settlements in Buenos Aires and with the privatised utility (Aguas Argentinas) to consider how privatised provision for water and sanitation can best meet the needs of low-income groups, especially those living in informal settlements.

HARDOY SCHUSTERMAN (2000): New Models for the Privatization of Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor. Buenos Aires: Environment & Urbanization URL [Accessed: 03.09.2010]Privatization of Water and Sanitation Services in Kenya: Challenges and Prospects

This document is about privatisation of water and sanitation services in Kenya. It includes some helpful recommendations after it describes the whole privatisation process with challenges and prospects in Kenya.

NYANGENA (2008): Privatization of Water and Sanitation Services in Kenya: Challenges and Prospects. Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa URL [Accessed: 02.09.2010]Water supply and privatization

On this website in German, many links can be found to different publications on privatisation in Africa. KOSA (Coordination Southern Africa) is very active in the sector of water and privatisation.