Executive Summary

The development of human resources is at the core of sustainable development. People and communities that are empowered with the necessary knowledge and skills will be the architects of their own development and able to confront a diverse set of challenges in a rapidly changing social, economic and environmental landscape. In the context of Sustainable Sanitation and Water Management, the challenge is to develop human capacities at all levels in order to provide adequate, equitable and sustainable services. Human capacity development therefore must include the capacity of the community as well as the organisations that work with them, facilitating a harmonious exchange and integration of local capacity and local knowledge with the external technical information and social skills. HRD is as much a process and a goal.

Introduction

The world is changing, and so is how we should approach sanitation and water resource management. The new paradigm is far more concerned with the impact or “footprint” of our human activities on the natural environment both in terms of the consequences of over exaction of water from aquatic ecosystems and subsurface aquifers, as well as the pollution of downstream systems with our untreated “waste”. This paradigm shift also involves a search for smaller decentralised sustainable systems which are generally more energy and resource efficient and environmentally friendly by closing water and nutrient loops. This approach also has important implications in terms of human resource development.

Human Resources Development (HRD)

Community Empowerment

In order to assure that the sanitation and water systems are contextually appropriate and will be adequately managed and maintained over time, it is essential to respect and support the central role of the end users and communities, and to involve them in all of the essential stages of the process – i.e. needs identification, selection of technical options, system design, and operation and maintenance (O&M). In other words, communities can no longer be viewed as passive beneficiaries, but rather as central actors whose capacities and knowledge need to be developed from the outset.

In this process, it is important to recognise the innate knowledge and skills of local people as the foundation upon which new capacities can be developed. Community people - and adults in general - learn best from experience (see adult learning) and, from this standpoint, often will have evolved certain attitudes and cultural norms that will make them more or less resistant – or open - (to considering and ultimately accepting new approaches and technologies that could be of personal and collective benefit. For his reason, it is critical that the external “change agents” have the necessary understanding, together with the educational and communication tools, in order to facilitate the sharing of diverse perspectives and “world views” to arrive at the appropriate solution for the specific situation (see also awareness raising (see PPT)).

Ultimately, the development of local capacity must include the facilitation of a positive self-image (self-esteem and self-confidence), good communication and organisational skills, as well as technical capacity to assure the necessary ongoing monitoring and maintenance of the systems. In order to adequately develop this range of capacities – attitudinal, information and skills – the best training process should be highly participatory and inclusive from the beginning, well before actual system infrastructure installation takes place; subsequently focusing more on the more directive delivery of technical information and skills; and finally a more internally driven approach where the users begin to assume their roles in the longer term operation, monitoring and sustainability of the systems.

It is important to recognise and appreciate that the additional cost and effort in the development of community human resources are an investment. It does not only benefit the long term sustainability of the particular systems that are being considered, but it also recognises the fact that community people are the primary building blocks of sustainable communities. Hence, the confidence, knowledge and skills generated in a particular project will be replicated and magnified over time in multiple community-based initiatives that will impact on the livelihoods and quality of life of all involved. Indeed, sustainable productive sanitation by definition must be a multi-sectoral, interdisciplinary effort involving most aspects of a healthy community – e.g. water, solid waste, agriculture, health, education, employment generation, architecture, environment, watershed management, etc. (see also planning and process tools section, which provides an overview of participatory approaches).

Professional Education and Training

As distinct from a normal adult experiential learning process, most water and sanitation sector professionals – e.g. sanitation engineers and practitioners, policymakers, managers, and operators – have acquired much of their information and ideas in a formal, top-down academic educational process, and tend to try to pass it on in the same vertical manner. But perhaps even more serious is the fact that “curricula of Universities, continuing education programs, technical schools, research institutes and training centres mostly continue to present conventional (centralised, waterborne) sanitation as the only legitimate approach.” (UNESCO-IHP & GTZ 2006). The urgent challenge then is to simultaneously transform not only WHAT the formal system teaches, but also HOW they teach. To a significant degree, formal academic institutions tend to continue to be “ivory towers”, with limited relevance to the real needs of the majority of the words underserved and attributing insufficient value to experiential learning and thus offering too few practical learning opportunities too late in a student’s career.

Educational institutions should:

- Fully integrate the discourse and criteria for sustainability into their curricula;

- View the primary stakeholders (users and local communities) not as objects, but as partners for jointly developing sustainable sanitation solutions.

- Prepare students to think about wastewater – urine and faeces and grey/black water – as resources;

- Make clear that health and a healthy environment is a prerequisite for human productivity, and productivity determines economic well being (UNESCO-IHP & GTZ 2006).

Finally, training centres and universities need to revise their curricula to provide much greater time in the field so that their student trainees can learn from the communities – or, at least, acquire the humility to recognise that their school learning is only half –if that– of the whole picture. Indeed, in many cases the university degrees are less important than the experiential/field learning itself. It is encouraging that many universities are being restructured to include extended practical internships with sector organisations and others, while the more progressive are actually giving greater emphasis to the experiential with the academic and research programs driven by field realities and demands (ESW 2011).

Institutional Staff HRD

It is also important that the development institutions themselves get their priorities straight. They should recognise that identifying the right people to do the jobs has to do not only with their formal preparation, but as well with their experience and commitment. Often, organisations make the mistake of being top-heavy, looking for people that are overly qualified and have a career path that is excessively upward mobile in institutional terms, thus minimising the value on field experience and commitment. In order to overcome this understandable and fairly natural tendency, there need to be incentive structures to keep qualified people in the field –and also the other way around, to get the “managers and technicians” out into the field. Another useful strategy is to develop a more pro-poor institutional staffing structure, which is more equitable and “flatter” in terms of salary scales and compensations. There should also be recognition of highly qualified people who have opted to work and keep themselves closer to the field. Moving to the "urban" head office should not be seen as the only way of being rewarded and remunerated for good performance.

Resource Centres

Resource centres – or nodes –, whether public or private, can play an important role in providing relevant and accessible HRD and support services, such as information management and dissemination, integrated training, applied research and consultancies. In addition to facilitating short courses in both technical and social themes for both the general public as well as tailor made for specific institutional and program contexts, resource centres, in partnership with universities and other more formal training institutes, can provide longer term training programs (e.g. diploma courses) with formal accreditation. Given their flexibility and closer proximity and contact with field programs and realities, resource centres can frequently play a strategic role in interpreting and translating field needs and demands, in order for the more formal academic institutions to adapt and respond with more relevant educational programs and information resources (EAWAG 2005).

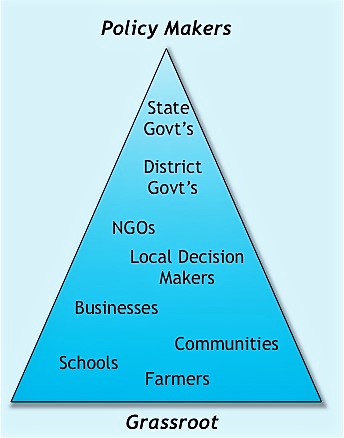

Many groups and organisations need training and orientation so that they can understand and support the integrated sustainable sanitation and water management approaches: householders need to understand the range and implications of the options open to them; CBOs, which undertake construction, O&M and/or management of local projects, will need training on technical matters, financial management, contract procedures and reporting; NGOs, which often have a critical role in providing training and direct support to communities and linking them with external resources, will need to develop communication, participatory training and other social as well as technical capacities; local government authorities and technical personnel can be assisted in acquiring a better understanding of the social, institutional, financial, as well as technical factors that have to be addressed; private providers can be encouraged through developing a range of skills in business management, loan applications, analysis of market demands, and exposure to a broader range of technical options to address different contexts and demands (see figure below).

In all these contexts, the training approach should be learner-centred (see also adult learning). In other words, beginning at the level of experience and understanding of the group of learners, in order to build from there, in a process of mutual respect, analysis and discovery of the appropriate solutions (EAWAG 2005).

Household-Centred Environmental Sanitation, Implementing the Bellagio Principles in Urban Environmental Sanitation – Provisional Guideline for Decision Makers

This guideline for decision-makers has been developed to provide first guidance on how to implement the Bellagio Principles by applying the HCES approach. Assistance is given to those willing to include and test this new approach in their urban environmental sanitation service programmes. Since practical experience with the HCES approach is lacking, this guideline is neither comprehensive nor final, but will have to be developed further on the basis of extensive field experience. Available in English, French and Spanish.

EAWAG (2005): Household-Centred Environmental Sanitation, Implementing the Bellagio Principles in Urban Environmental Sanitation – Provisional Guideline for Decision Makers. Geneva, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology URL [Accessed: 17.06.2019]Capacity Building for Ecological Sanitation

This publication deals with the educational aspects linked to ecologically sustainable sanitation, and contains extensive chapters on capacity building and knowledge management in the field of ecological sanitation.

UNESCO/IHP ; GTZ (2006): Capacity Building for Ecological Sanitation. Paris & Eschborn: German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) & International Hydrological Programme of UNESCO (UNESCO/IHP) URL [Accessed: 15.04.2019]Engineers for a sustainable world - Website

Capacity Building for Ecological Sanitation

This publication deals with the educational aspects linked to ecologically sustainable sanitation, and contains extensive chapters on capacity building and knowledge management in the field of ecological sanitation.

UNESCO/IHP ; GTZ (2006): Capacity Building for Ecological Sanitation. Paris & Eschborn: German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) & International Hydrological Programme of UNESCO (UNESCO/IHP) URL [Accessed: 15.04.2019]Household-Centred Environmental Sanitation, Implementing the Bellagio Principles in Urban Environmental Sanitation – Provisional Guideline for Decision Makers

This guideline for decision-makers has been developed to provide first guidance on how to implement the Bellagio Principles by applying the HCES approach. Assistance is given to those willing to include and test this new approach in their urban environmental sanitation service programmes. Since practical experience with the HCES approach is lacking, this guideline is neither comprehensive nor final, but will have to be developed further on the basis of extensive field experience. Available in English, French and Spanish.

EAWAG (2005): Household-Centred Environmental Sanitation, Implementing the Bellagio Principles in Urban Environmental Sanitation – Provisional Guideline for Decision Makers. Geneva, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology URL [Accessed: 17.06.2019]Ecovillages - Academia

In this article, Daniel Greenberg, shows what academia and ecovillages can gain from one another. He argues that together, ecovillages and academia can transform higher education into a rich soil that grows knowledge and projects that support the regeneration of our planet. The full book can be downloaded from http://www.gaiaeducation.org/docs/Beyond%20You%20&%20Me%20Ebook.pdf.

GREENBERG, D. (2007): Ecovillages - Academia. In: JOUBERT, K.A. and ALFRED, R. (eds). Beyond you and me. Inspirations and Wisdom for Building Community. Hampshire (UK): Permanent Publications, pp.236-242. [Accessed: 25/05/2011] . .How to Create a Regional Dynamic to Improve Local Water Supply and Sanitation Services in Small Towns in Africa

Small towns, the size of which can vary from between 3,000 and 30,000 inhabitants, have specific characteristics as they tend to be situated midway between rural and urban. Too small to benefit from those opportunities available to large urban centers, particularly in terms of competencies for developing and managing services, they are also too large to be able to accommodate those community-based approaches prevalent in rural areas. This guide defines the specific issues and challenges facing small towns. A methodology for developing a regional strategy for water and sanitation is provided, as well as the courses of action to be followed to facilitate access to finance and mobilize the expertise required to provide back-up support and training to local authorities and service operators.

VALFREY-VISSER, B. (2010): How to Create a Regional Dynamic to Improve Local Water Supply and Sanitation Services in Small Towns in Africa. (= Six Methodological Guides for a Water and Sanitation Services' Development Strategy , 2 ). Cotonou and Paris: Partenariat pour le Développement Municipal (PDM) and Programme Solidarité Eau (pS-Eau) URL [Accessed: 19.10.2011]Block Mapping Procedures

This manual is part of a Utility Management Series for Small Towns. It can be used either as a training module to support the delivery of capacity building programmes in utility management and operations or as a reference manual to guide operations and maintenance staff in designing and implementing programmes in Block Mapping. The Manual introduces the concept and procedure of “Block mapping”, which aims at sub dividing the water and sewerage services area so that developments and services can be clearly mapped.

UN-HABITAT (2013): Block Mapping Procedures. (= Utility Management Series of Small Towns , 3 ). Nairobi: UN-HABITAT URL [Accessed: 28.03.2013]A Global Review of Capacity Building Organizations in Water Sanitation, and Hygiene for Developing Countries

This study attempts to review the global capacity building efforts in the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) sector by identifying the major capacity building organizations, understanding their focus and activities, comparing their efforts, and assessing potential gaps in capacity building services.

NGAI, T.K.K. MILLS, O. FRENCH, G. OLIVEIRA, R. LEPORE, C. MATTENS, M. SIBANDA, T. SWEET, M. GRAVES, A. (2013): A Global Review of Capacity Building Organizations in Water Sanitation, and Hygiene for Developing Countries. (= conference paper 36th WEDC International Conference, Kenya 2013). Loughborough: Water, Engineering and Development Center (WEDC)Human Resource Capacity Gaps in Water and Sanitation

This is the synthesis report of the Human Resource Capacity Assessments. In the water and sanitation sector, the human resource requirement to meet the water and sanitation targets has been relatively unknown in relation to the numbers of staff, qualifications and their practical experience. IWA developed an assessment method to collect data on human resource gaps (skills) and shortages (number of workers) at the national level in the water and sanitation sector. The assessment method was piloted in five countries in 2009, Mali, Zambia, South Africa, Bangladesh and Timor L’este and in phase 2 a more structured approach was used for 10 in-country assessments (Burkina Faso, Tanzania, Mozambique PNG, Sri Lanka, Lao PDR and Philippines, Niger, Senegal, and Ghana).

IWA (2013): Human Resource Capacity Gaps in Water and Sanitation. Main Findings and the Way Forward. London: International Water Association (IWA) URL [Accessed: 16.04.2019]Training in Community-Led Total Behavior Change in Hygiene and Sanitation: The Amhara Experience in Line with the Health Extension Program

This manual provides a comprehensive training to build capacity of health extension workers (HEWs) and development agents to support total behavior change in hygiene and sanitation. Complete with exercises, facilitators notes, and tools.

WSP ; USAID-HIP (2009): Training in Community-Led Total Behavior Change in Hygiene and Sanitation: The Amhara Experience in Line with the Health Extension Program. Facilitators Guide. Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: Amhara National Regional State Health Bureau, World Bank Water and Sanitation Programme (WSP), USAID Hygiene Improvement Project (USAID-HIP) URL [Accessed: 24.06.2019]IRC WASH Library

The IRC WASH Library acts as WASH Sector memory documenting more than 40 years of sector progress, analysis and tools. The library provides direct access to a still increasing number of WASH sector documents.

Ecosan Training Programs

Ecosan Services Foundation is an NGO raising the awareness on sustainable sanitation in India, and carrying out training courses with different target groups in South Asia.

Sustainable Sanitation Center (SUSAN Center)

The Sustainable Sanitation Center (SUSAN Center) is a multidisciplinary convergence center of Xavier University. The SUSAN center is committed to a science-based and multi-sectoral engagement in sustainable sanitation, aiming to achieve a cleaner and healthier environment and promoting human dignity for peaceful and sustainable development in Mindanao, the Philippines and the wider Southeast Asian region. The SUSAN centers core activities include capacity development of communities, policy makers and other institutions on sustainable sanitation and to support the development and implementation of various sustainable sanitation technology solutions.

cewas - The business and integrity experts in the water sector

cewas is a Swiss-based international centre of competence in the field of sustainable sanitation and water resource management. It combines advanced education with a start-up centre, a think tank, and a business platform.

SuSanA - Knowledge Hub

This part of the website of the Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA) provides you with an overview of education material on sustainable sanitation.