Resumen ejecutivo

Water and wastewater tariffs determine the level of revenues that service providers receive from users in centralised or semi-centralised systems for the appropriate catchment, purification and distribution of freshwater, and the subsequent collection, treatment and discharge of wastewater. Water pricing is an important economic instrument for improving water use efficiency, enhancing social equity and securing financial sustainability of water utilities and operators. Tariff setting practices vary widely around the world. Here, we will introduce the increasing block tariff as type of step-wise volumetric charge commonly used in many countries.

Block Tariffs

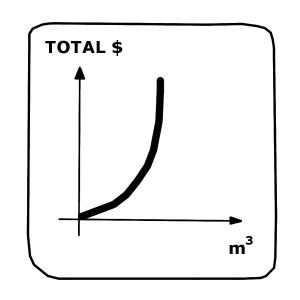

Block tariffs are volumetric charges. The prerequisite for setting a volumetric charge is that consumers have a metered connexion to water services. Under a block tariff scheme, users pay different amounts for different consumption levels. Block tariffs have a step-wise structure. The water charge is set per unit (e.g. cubic meters) of water consumed and remains constant for a certain quantity of consumption (first block). As the water use increases, the tariff shifts to the next block of consumption and so on for each block of consumption until the highest one. Block tariffs can be differentiated among consumer categories (e.g. domestic and non domestic) and are of two main types: increasing and decreasing.

Increasing Block Tariff

(Adapted from WHITTINGTON 2002)

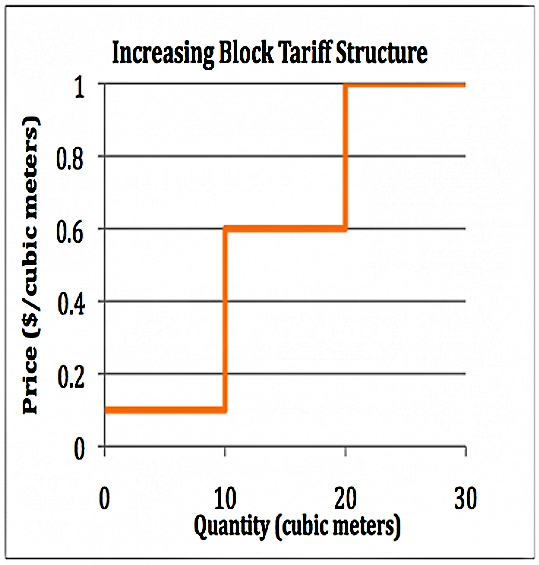

With increasing block tariffs, the rate per unit of water increases as the volume of consumption increases. Consumers face a low rate up to the first block of consumption and pay a higher price up to the limit of the second block, and so on until the highest block of consumption. At the highest block consumers can use as much water they desire, but for each additional water unit consumed they pay the highest price in the rate structures (see example below the tariff structure in La Paz-Bolivia). Increasing block tariffs are by far the most common charges for water services. They are used in countries were water has been historically scarce such as in Spain and the Middle East and they are widespread in developing countries.

Design Principles of Increasing Block Tariff

In order to design an increasing block structure, the regulator must decides for each category of water use:

- The number of blocks.

- The volume of water use associated with each block.

- The prices to be charged for water use within these blocks.

Water blocks design is generally based on consumption pattern of the public and on per capita water consumption norms defined for local bodies (TERI 2010).

An ideal progressive tariff structure would contain 3 blocks:

- A social or lifeline block with a volume of water corresponding to the essential minimum consumption, (e.g. 4 to 5 m3 per month and household (5 persons), corresponding to the minimal needs)

- A “normal” block corresponding to the average consumption defined on the basis of the marginal cost (e.g. from 5 to 12 or 15 m3 per month for a standard family of 5)

- A high block above 12 or 15 m3 per month set at a price designed to finance the full cost of the service

The first block, also called lifeline block is normally set below cost.The aim is to provide the poor with inexpensive water, while charging the highest prices to richer customers and companies — who are known to use more water and have a greater ability to pay. By charging higher prices for high consumption, increasing block tariffs are also meant to discourage excessive water use. Increasing block tariffs can be also designed as a two-part tariff. In that case, in addition to a variable tariff based on consumption, a monthly fixed rate is charged for all consumers (CARDONE & FONSECA 2003).

In reality, block tariffs are often more complex and the design process is not always transparent.

Example: Increasing Block Tariffs in La Paz – Bolivia

(Adapted from BOLAND & WHITTINGTON 2000)

The following example of increasing block tariff in La Paz (Bolivia) is representative of increasing block tariffs currently used in many developing countries.

The table below illustrates the increasing block tariff adopted in 1997 from the municipality of la Paz together with the local water utility (SAMAPA) and the Bolivian national tariff board.

| Volumetric charge (US $ per cubic meter) | Domestic water connexions | Commercial water connexions | Industrial water connexions |

| 0.22 | 1 to 30 m3 |

|

|

| 0.44 | 31 to 150 m3 |

|

|

| 0.66 | 151 to 300 m3 | 1 to 20 m3 |

|

| 1.18 | Above 300 m3 | Above 20 m3 | All water |

Notes: 99% all residential consumers use less than 150 m3 per month. The long run marginal cost is estimated at US $ 1.18 per month. Source: BOLAND & WHITTINGTON (2000)

The progressive rate structure in La Paz differentiates between user categories (domestic, commercial and industrial) and was developed to subsidise residential consumer using low volume of water. In la Paz, there are four blocks for residential connexions, two blocks for commercial connexion and one block for industrial connexions. Domestic charges face large price differentials between consumption blocks (the highest rate is five times the lowest one). Charges for commercial and industrial water users are much higher than those applied for typical domestic consumption level.

Critical Issues Related to Increasing Block Tariff

Problems related to increasing block tariff structure are discussed below by means of the example of La Paz, as this well represents typical progressive structures used in many developing countries.

The design of the lifeline block is a delicate issue as it is rife with social implications. Regulators may be reluctant in limiting the size of the initial block because of political pressures (BOLAND & WHITTINGTON 2000). In the case of La Paz, the limit of the first block of consumption is set at 30 m3, which is considered to be too large (for a family of 5, it means that they can use 200L of water per day at the lowest tariff, which is quite a high amount; e.g. does an average person in Switzerland use ca. 160 L person/day). Households using less of 30 m3 per month are not able to save on their water bill and also non-poor households are profiting from the lifeline tariff. Furthermore, water can be resold at much higher prices at households without connexion to the water services. Economic criteria of efficiency require that prices reflect the marginal cost of the service provided. In La Paz water for residential users is priced at marginal cost only for units above 300 m3, corresponding at the fourth (highest) block of consumption. However, most households use less than 150 m3 water per month, therefore very little water is actually sold at marginal cost contributing to investments in the water and sanitation system.

In some cases increasing block tariffs may have unintended effects on the poor. In theory, low-income households with private metered connexion benefit from the subsidised rate, but this is not always the case if poor households are sharing a single connexion — as it is for example very common in India — that drives consumption and rates higher, with the result that poor households finally pay more than better-off users. Moreover, in developing countries, most of poor households have no connexions to the water distribution system therefore they are not in a position to be helped by the lifeline tariff (CARDONE & FONSECA 2003).

“One alternative to correct some of the inefficiencies of increasing block tariffs would be to charge the same price per unit for all income groups and add a fixed charge for different income groups. For the poorest, this would mean a negative fixed charge to be deducted from the volumetric charge. Nevertheless, this proposal assumes that the poor can be easily identified and the whole process involves high administrative costs” (CARDONE & FONSECA 2003).

Learn more on other types of water pricing:

- general information on water pricing

- decreasing block tariffs

- fixed water charge

- uniform volumetric charge

Increasing block tariffs are applicable everywhere where water is provided and/or wastewater is collected. However, a metering system is required. Block tariffs can be set at the service-provider level or by national or local government. Involvement of local communities in the tariff setting process is important to identify the real local needs, the costs of providing a good quality service, and the best ways to recover the costs incurred (CARDONE & FONSECA 2003).

Water Tariff Design in Developing Countries: Disadvantages of Increasing Block Tariffs and Advantages of Uniform Price with Rebate Designs

Financing and Cost Recovery

This paper provides an excellent overview on financing and cost recovery for the water supply and sanitation services sector in rural and low-income urban areas of developing countries. The document contains also case studies and mini reviews of best publications on financing and cost recovery.

CARDONE, R. FONSECA, C. (2003): Financing and Cost Recovery. Delft (The Netherlands): IRC (International Water and Sanitation Centre). Thematic Overview Paper 7. URL [Visita: 03.05.2019]A Framework for Analyzing Tariffs and Subsidies in Water Provision to Urban Households

This paper aims to present a basic conceptual framework for understanding the main practical issues and challenges relating to tariffs and subsidies in the water sector in developing countries. The paper introduces the basic economic notions relevant to the water sector; presents an analytical framework for assessing the need for and evaluating subsidies; and discusses the recent evidence on the features and performance of water tariffs and subsidies in various regions, with a special focus on Africa. The discussion is limited to the provision of drinking water to urban households in developing countries.

BLANC, D. le (2008): A Framework for Analyzing Tariffs and Subsidies in Water Provision to Urban Households . New York: DESA Working Paper n°63 URL [Visita: 20.07.2010]Water is an Economic Good: How to use Prices to Promote Equity, Efficiency, and Sustainability

This paper focuses on the role of prices in the water sector and how they can be used to promote equity, efficiency, and sustainability.

ROGERS, P. ; SILVA, R. de ; BATHIA, R. (2001): Water is an Economic Good: How to use Prices to Promote Equity, Efficiency, and Sustainability. Entradas: Water Policy : Volume 4 , 1–17. URL [Visita: 03.05.2019]Review of Current Practices in Determining User Charges and Incorporation of Economic Principles of Pricing of Urban Water Supply

This report reviews current practices in determining user charges and researches how economic principles of pricing of urban water supply can be incorporates. It researches international practices in the UK, Australia and the Philippines and several cases in India.

TERI (2010): Review of Current Practices in Determining User Charges and Incorporation of Economic Principles of Pricing of Urban Water Supply. New Delhi: TERI URL [Visita: 03.05.2019]Tariffs and Subsidies in South Asia: Understanding the Basics

Municipal Water Pricing and Tariff Design: a Reform Agenda for South Asia

This paper describes the major elements of a package of pricing and tariff reforms that are needed in the municipal water supply sector in many South Asian cities. Keywords: Increasing block tariffs; Pro-poor policies; Seasonal tariffs; Subsidies; Tariff designs; Water pricing.

WHITTINGTON, D. (2003): Municipal Water Pricing and Tariff Design: a Reform Agenda for South Asia. Entradas: Water Policy 5 : , 61–76. URL [Visita: 20.07.2010]Pricing Water and Sanitation Services. Human Development Report 2006. Human development office-occasional paper

The purpose of this paper is to provide the reader with a better understanding of the main issues involved in the design of W&S tariffs. Keywords: Costs of W&S services, objectives of tariff design, tariff options, subsidies, development paths of W&S services.

WHITTINGTON, D. (2006): Pricing Water and Sanitation Services. Human Development Report 2006. Human development office-occasional paper. New York: UNDP URL [Visita: 03.05.2019]Pricing Water and Sanitation Services. Human Development Report 2006. Human development office-occasional paper

The purpose of this paper is to provide the reader with a better understanding of the main issues involved in the design of W&S tariffs. Keywords: Costs of W&S services, objectives of tariff design, tariff options, subsidies, development paths of W&S services.

WHITTINGTON, D. (2006): Pricing Water and Sanitation Services. Human Development Report 2006. Human development office-occasional paper. New York: UNDP URL [Visita: 03.05.2019]Financing and Cost Recovery

This paper provides an excellent overview on financing and cost recovery for the water supply and sanitation services sector in rural and low-income urban areas of developing countries. The document contains also case studies and mini reviews of best publications on financing and cost recovery.

CARDONE, R. FONSECA, C. (2003): Financing and Cost Recovery. Delft (The Netherlands): IRC (International Water and Sanitation Centre). Thematic Overview Paper 7. URL [Visita: 03.05.2019]Providing Water to the Urban Poor in Developing Countries: The Role of Tariffs and Subsidies

This brief explores the role of water tariffs and subsidies as key instrument to achieve the objective of providing safe and affordable drinking water to residents of growing urban areas in developing countries.

BLANC, D. le (2007): Providing Water to the Urban Poor in Developing Countries: The Role of Tariffs and Subsidies. Entradas: Sustainable Development Innovation Brief: Volume 4 URL [Visita: 03.05.2019]A Framework for Analyzing Tariffs and Subsidies in Water Provision to Urban Households

This paper aims to present a basic conceptual framework for understanding the main practical issues and challenges relating to tariffs and subsidies in the water sector in developing countries. The paper introduces the basic economic notions relevant to the water sector; presents an analytical framework for assessing the need for and evaluating subsidies; and discusses the recent evidence on the features and performance of water tariffs and subsidies in various regions, with a special focus on Africa. The discussion is limited to the provision of drinking water to urban households in developing countries.

BLANC, D. le (2008): A Framework for Analyzing Tariffs and Subsidies in Water Provision to Urban Households . New York: DESA Working Paper n°63 URL [Visita: 20.07.2010]Water is an Economic Good: How to use Prices to Promote Equity, Efficiency, and Sustainability

This paper focuses on the role of prices in the water sector and how they can be used to promote equity, efficiency, and sustainability.

ROGERS, P. ; SILVA, R. de ; BATHIA, R. (2001): Water is an Economic Good: How to use Prices to Promote Equity, Efficiency, and Sustainability. Entradas: Water Policy : Volume 4 , 1–17. URL [Visita: 03.05.2019]Municipal Water Pricing and Tariff Design: a Reform Agenda for South Asia

This paper describes the major elements of a package of pricing and tariff reforms that are needed in the municipal water supply sector in many South Asian cities. Keywords: Increasing block tariffs; Pro-poor policies; Seasonal tariffs; Subsidies; Tariff designs; Water pricing.

WHITTINGTON, D. (2003): Municipal Water Pricing and Tariff Design: a Reform Agenda for South Asia. Entradas: Water Policy 5 : , 61–76. URL [Visita: 20.07.2010]International Statistics for Water Services

This short leaflet presents water international statistics for water services, e.g. major cities’ water bills, abstraction sources for drinking water supplies, or a large comparison of water cycle charges.

IWA SPECIALIST GROUP STATISTICS AND ECONOMICS (2010): International Statistics for Water Services. The Hague: International Water Association (IWA). [Accessed: 22.04.2012] PDFWater and Sanitation

The website of UN DESA (UN Department of Economic and Social Affaires) contains a section dedicated to water issues, including publications about water tariffs and subsidies in the provision of water services in developing countries.

World Water Assessment Programme (UNESCO WWAP)

The website of the World Water Assessment Program (WWAP) serves as a thematic entry point to the current UNESCO and UNESCO-led programmes on freshwater. It offers a review of case studies to highlight the challenges that need to be addressed in the water resources sector including water-pricing issues.